A Window into the Cosmos

University scientists among team confirming Einstein’s theory of relativity

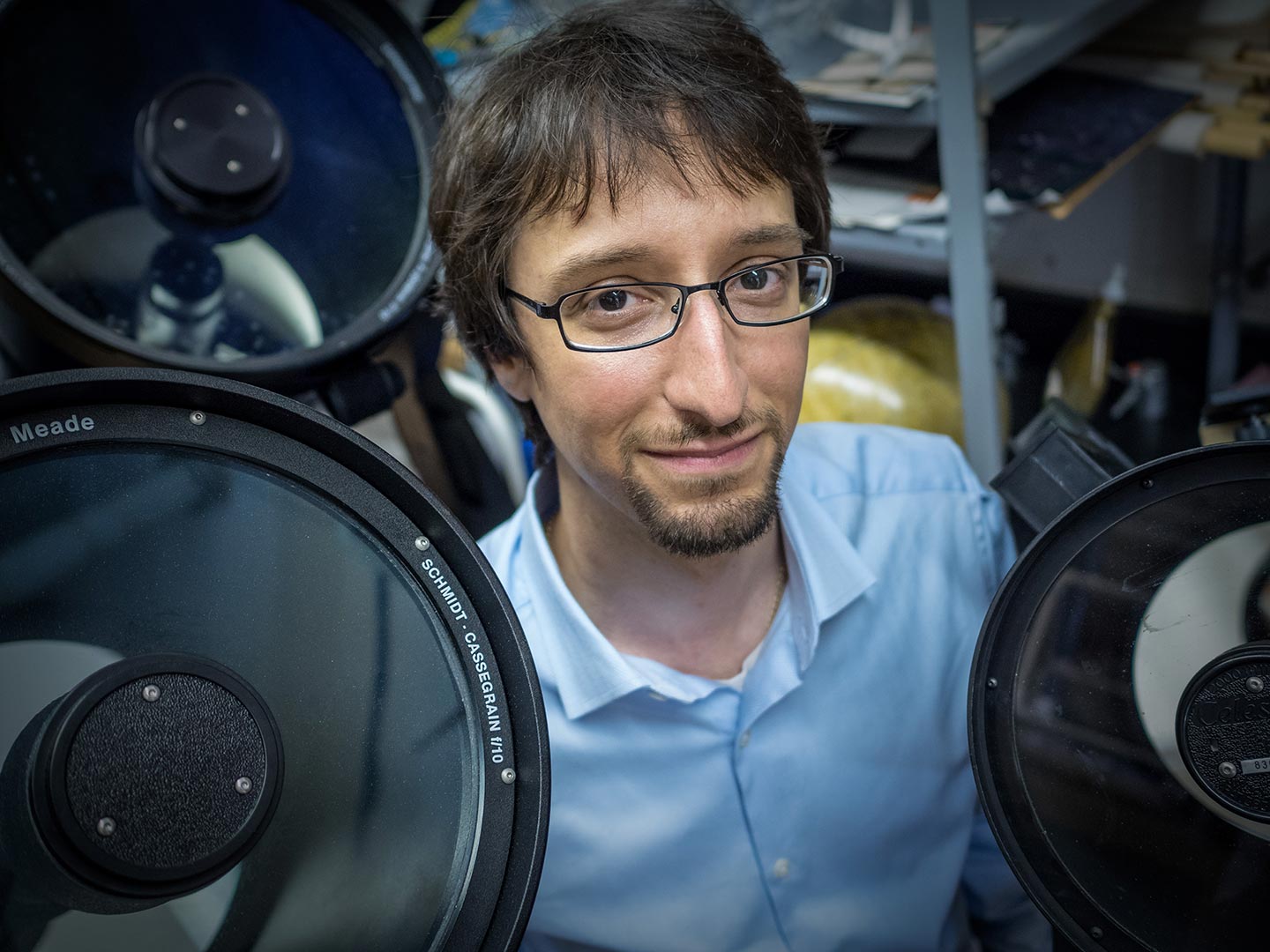

Physics Professor Marc Favata and two students became a part of scientific history in February when the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the detection of gravitational waves by the LIGO twin detectors in September 2015. This confirms a major prediction of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity and opens an unprecedented new window into the cosmos.

Favata, a LIGO member, along with senior Blake Moore and recent BS/MS graduate Goran Dojcinoski, co-authored the paper describing the detection. “For the first time, we will be able to ‘listen’ to the universe and explore the nature of black holes in a totally new way,” says Favata. “Gravitational waves are ripples on the ocean of spacetime. By directly detecting these waves with Earth-based instruments, we are opening up a new field of astronomy. Previously we could only ‘see’ the universe; now we’ll be able to ‘hear’ it.”

Gravitational waves carry information about their dramatic origins and about the nature of gravity that cannot otherwise be obtained. Physicists have concluded that the detected gravitational waves were produced during the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole. This collision of two black holes had been predicted but never observed.

The gravitational waves were detected on September 14, 2015, at 5:51 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time by both of the twin LIGO detectors, located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. The LIGO detectors are funded by the National Science Foundation, and were conceived, built and are operated by Caltech and MIT. The discovery, accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters, was made by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (which includes the GEO Collaboration and the Australian Consortium for Interferometric Gravitational Astronomy) and the Virgo Collaboration using data from the two LIGO detectors.

“For the first time, we will be able to ‘listen’ to the universe and explore the nature of black holes in a totally new way.”

Based on the observed signals, LIGO scientists estimate that the black holes in this event were about 29 and 36 times the mass of the sun, and the event took place 1.3 billion years ago. About three times the mass of the sun was converted into gravitational waves in a fraction of a second – with a peak power output about 50 times that of the whole visible universe. By looking at the time of arrival of the signals – the detector in Livingston recorded the event 7 milliseconds before the detector in Hanford – scientists can say that the source was located in the Southern Hemisphere.

The work of the LIGO group at Montclair State is focused on improving the mathematical models of the gravitational-wave signal. Better models will allow the properties of colliding black holes or neutron stars to be determined more accurately. Montclair State became a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration in 2013, about a year after Favata joined the faculty.