Still, She Persists

Professor explores the cost of being a girl and the roots of pay inequity

Sociology Professor Yasemin Besen-Cassino has always been a feminist. “I grew up in Istanbul, Turkey, with feminist, working parents, who had a big effect on me,” she recalls. “Issues of gender equality are universal – regardless of place.”

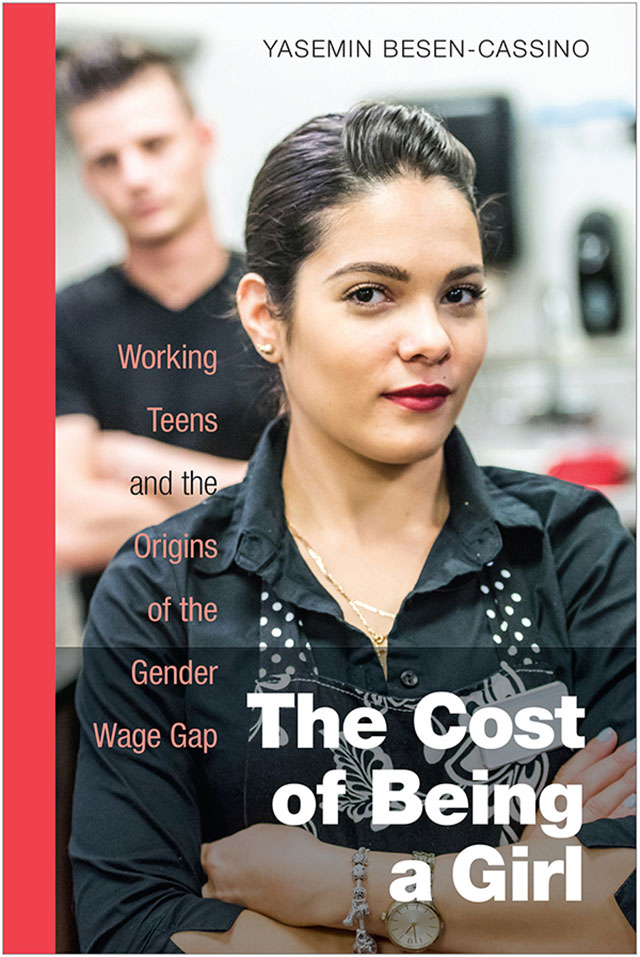

Long a vocal gender-equality advocate, Besen-Cassino spoke alongside Lily Ledbetter in support of the historic 2009 Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act and has testified as an expert witness before the New Jersey State Legislature. As a nationally recognized expert in gender pay equality, she has distilled her research into two well-received books, which have redefined the origins of the gender wage gap. Despite the slow progress in closing the wage gap, Besen-Cassino persists in challenging gender-based assumptions – including with new findings that suggest that even when wives earn more than their husbands, husbands do fewer household chores.

The wage gap starts early

While women make up nearly half of today’s workforce, they earn 20 percent less than their male counterparts. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, the earnings gap is unlikely to close anytime soon: at the current rate of change, it will be another 41 years before women achieve pay equity.

In determining the causes of the gender wage gap, Besen-Cassino defies traditional thinking. “I think we are looking at it the wrong way,” says the one-time Montclair State University Distinguished Scholar of the Year. “Pay explanations like babies and housework don’t really work. In my heart, I knew these explanations weren’t right, so I looked for ways to prove this,” she recalls. “I ultimately found that pay gap issues start in the teen years.”

Besen-Cassino first pinpointed the origins of the gender wage gap in her 2014 book, Consuming Work: Youth Labor in America, which discussed how early work experiences not only create and sustain socio-economic inequalities, but also create lasting gender inequality in the workplace. After tracking the same girls for many years, Besen-Cassino discovered that working as a teenager helps boys – but not girls. “Even many decades later, women who worked as teenagers make less money,” she says.

Her latest book, The Cost of Being a Girl, published in 2018 by Temple University Press, amplifies a chapter from Consuming Work, which found that while 12- and 13-year-old boys and girls earn the same money for babysitting, yard work or snow shoveling, by 14 and 15, the first gender wage gap emerges.

How girls pay the price

Besen-Cassino found that once teens are old enough to work for businesses, boys seamlessly move into these jobs while girls often stay in freelance work like babysitting. But this is not the only factor behind the start of the gender pay gap. “Boys have networks that tell them what a job might pay, so they are better equipped to negotiate their wages. When they negotiate, boys always get the money. Girls don’t,” she contends.

In retail jobs especially, girls often have no idea of what the pay should be before they negotiate, making it easy for would-be employers to exploit them by assuming they want to work for the employee discount and don’t really care about earning money. “They are told they know the brand, and are good with people,” Besen-Cassino says.

The wage gap is even wider for teens of color and lower-income girls who are less likely to conform to the image sought by corporate employers. “These look requirements make it seem like it’s their fault for not having the right outfits.”

In the end, all teen girls who work pay a steep psychological toll, especially in the apparel industry where they internalize gendered and unfair workplace assumptions about weight and appearance.

“Parents can only do so much to fix this. We tell our kids they can be anything they want, but kids don’t believe this, once they experience job inequity firsthand,” she insists.

Besen-Cassino believes that as a society, active steps need to be taken to turn things around. “Without changing the structural problems of the workplace, we cannot simply continue to tell our teenagers that it’s going to be okay.”

Working for change

Besen-Cassino is nonetheless hopeful that real change will occur. In January, Iceland became the first nation to make it illegal for companies with more than 25 employees to pay men more than women. Closer to home, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy has signaled his support for equal pay for women by signing an executive order prohibiting managers in state government from questioning potential employees about previous salaries. “This was really encouraging, as it was the first thing he signed when he became governor in January,” she says.

She is equally heartened by how women’s voices have gained new strength – from the past two Women’s Marches to the growing momentum of the #MeToo movement. “This gives us hope as women. Women can’t take it anymore and are deciding as a group how to take action and change laws,” she says.

When men don’t work, they cook

These times are also changing – and challenging – for men. Recently, Besen-Cassino and her husband Dan Cassino, a political science professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University, have been looking at how men respond when they feel their masculinity is threatened.

They are studying what happens when women in heterosexual relationships become the new breadwinners after husbands or male partners lose their jobs or earn less money. “In conservative households, the husbands vote for Trump – and do less housework,” Besen-Cassino reports. In fact, the more wives outearn their husbands, the less housework the husbands will do – with one exception. “The more money their wives earned, the more time the men in the study – regardless of their politics – devoted to cooking.”

As cooking gains traction as a manly pastime that showcases mastery and skill, can the de-gendering of vacuuming, dishwashing and child care be far behind? Besen-Cassino and her husband intend to answer that question in a future book.