Hands-On History

by Amy Wagner

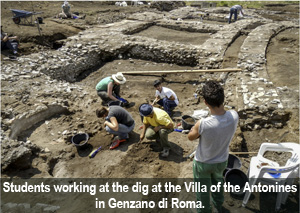

As students sift through layers of dirt at an Italian archaeological site, the mercury heads for 100 degrees, but they barely notice – so engrossed are they in the discoveries they’re making.

The students are taking part in Montclair State’s archaeological dig at the Villa of the Antonines in Genzano di Roma, Italy, where they are unearthing long-buried secrets of life during the Roman Empire, including an amphitheater quite possibly used by ruler Commodus as a gladiator practice arena.

For the past four summers, Montclair State undergraduate and graduate students have excavated the site of the ancient villa complex. They have been accompanied by students from schools like Brown University, Fordham University, the University of Minnesota, Johns Hopkins University, SUNY Albany and Centenary College of Louisiana, who can all join Montclair State’s field school for a month.

Every weekday morning at 7:30, the 11 students on the dig this past summer were shuttled from their hotel to the site. The budding archaeologists worked until around noon, when they would seek the shade of a mesh-covered wood shelter to break for a three-course lunch of pasta, meat or vegetables and fresh fruit delivered by their hotel. “The food was wonderful,” recalls Montclair State junior Katherine Sferra. “Everyone made fun of me because I insisted on taking a picture of every meal before we ate it.” Their workday ended at around 4:30 in the afternoon, when they were free to explore the region on their own.

“The Alban Hills, where our site is located, was one of the very first places Roman emperors built imperial villas,” says Professor Deborah Chatr Aryamontri, who co-directs the Montclair State Center for Heritage and Archaeological Studies Field School program with Professor Timothy Renner. “This was a pleasant place where the elite would go in the summer to escape the stifling heat of Rome.”

I, Commodus

I, Commodus

In 2010, the classics and general humanities professors began excavating the villa, located near the 18th-mile marker of the Appian Way in the area once known as Lanuvium.

Each year since then, Italian students from the University of Rome-La Sapienza also have taken part in the dig. “They generally have degrees in archaeology and solid field experience,” notes Renner.

Chatr Aryamontri studied at La Sapienza, where she developed strong ties with the Italian archaeological community. Thanks to her extensive training in classical field archaeology, the Italian government granted Montclair State exclusive permission to excavate the historic “Villa of the Antonines” site.

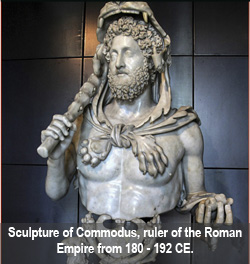

The professors subscribe to the theory that the complex belonged to the second-century CE Antonine dynasty that included emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. “We think Antoninus Pius would surely have owned this villa,” says Renner.

Commodus – perhaps best known as the inspiration for the crazed nemesis of the title character in the movie Gladiator – killed animals in the amphitheater unearthed by the Montclair State team. Convinced he was the reincarnation of Hercules, his rocky rule from 180–192 CE began the decline of the Roman Empire.

Cicero stopped here

Cicero stopped here

A centuries-old map depicts ancient remains outside of Genzano di Roma. “Accounts of contemporary travelers tell us its structures – including residences and an aqueduct – were impressive,” explains Renner. Statesman and orator Cicero was among the famous Romans who stopped or passed through ancient Lanuvium.

As the professors and students learn more from the site each year, they will eventually be able to place the “Villa of the Antonines” within the broader context of the region’s other imperial villas. “Originally, this villa may have been comparable to Hadrian’s in Tivoli, but it would be hard to tell for certain, as some buried parts have been destroyed by modern development. We are left with baths and an amphitheater-like structure,” says Renner. The team is assembling information, not only from the excavation, but from archival records of finds in the area, observations by earlier archaeologists and field surveys of neighboring properties, to develop a more complete picture of the entire complex.

“It’s possible that gladiatorial games and exhibits were held in that amphitheater,” adds Chatr Aryamontri. Stamped inscriptions on bricks in the amphitheater suggest that it could even have been an arena where Commodus, who was obsessed with gladiatorial combat, battled with lions and bears.

Handling history

Handling history

“I went to Italy in 2012 as an undeclared major,” recalls Sferra. “When it was time for me to declare a major, I looked back on my experience there and chose anthropology.” She says she felt compelled to return to the dig this past summer. “I felt like I’d started reading a book and needed to know how it ended.”

For Brian Montalbano, who is pursuing a master’s degree in history at Montclair State, the program appealed to his passion for ancient history and classics. A first-time participant in the program in 2013, he was excited to do meaningful work in his academic field. “I’ve read through pages of history, but how often do you get to put your hands on history?” he says.

Work this past summer continued on saggio A – or test trench A – of the roughly six-acre excavation site. Excavations also proceeded on a spiral staircase leading to an underground chamber discovered in the amphitheater in 2012. These efforts further defined the relationship of the amphitheater to the site’s adjacent bath complex.

“I loved finding glass tesserae – the small, colored tiles that once formed a mosaic,” Sferra says. There were days when she and other students carefully removed thousands of years of accumulated dirt from the glass fragments with toothbrushes. The dig has also unearthed marble fragments from North Africa and the Aegean region that were used for flooring and wall decorations, ceramic roof tiles and pieces of cookware, nails and even a coin of the Emperor Caligula.

“One of our most incredible finds was a large portion of a clay pot that was far more intact than usual,” notes Sferra. With a discovery like that, students summon the professors before painstakingly unearthing it – often using dental tools. “We take measurements to map where it was found and photograph it in situ and after it is removed from the ground,” she explains. Every find, whether large or small, is cleaned, bagged and labeled.

When in Rome . . .

The summer program gives students hands-on experience in every facet of an archaeological dig, from recordkeeping and cataloging artifacts to mapping and field surveys and, of course, unearthing relics.

Workshops on topics ranging from geophysical surveys to the meaning of artifact inscriptions are held on-site and at the Museo delle Navi Romane – a museum housing Caligula’s famous ships in nearby Nemi – thereby rounding out the educational experience. “An Italian archaeologist led a workshop on marble,” recalls Sferra. “I gained a much better understanding of the marbles I was finding on site. Plus, I learned that you can identify one type of white marble by licking it to see if it tastes like sulfur.”

Montclair State has “excellent relationships with the town of Genzano di Roma, the director of the Museo delle Navi Romane and fellow archeologists working in the area,” Chatr Aryamontri says. “Montclair State is part of a well-connected archaeological community.” Each season, the University team collaborates with Italian geophysicists from the University of Rome who conduct non-invasive geophysical site surveys to map what is buried below ground.

At the end of the summer, after covering the work area with tarps and sand to prevent weed growth, the group heads home. But for Renner and Chatr Aryamontri, the work has barely begun.

“We bring lists of our discoveries, drawings, rubbing of brick stamps, photos and day-to-day journal entries back to campus,” says Renner. “We need to document all the work done on site and report on the significance of our findings each season in order to get permission from Italian authorities to continue our work the following year.”

Renner and Chatr Aryamontri, who also deliver scholarly papers at conferences, describe their field work as both tantalizing and frustrating. “We’ve learned so much already,” says Renner, “but it takes time to put all the pieces of the puzzle together, and we want to learn so much more.”