Gareth B. Matthews

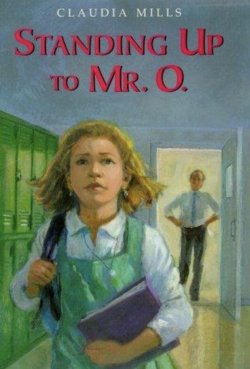

Review of Standing Up to Mr. O by Claudia Mills (New York: Hyperion, 2000). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 16(2): 3.

In her fifth-grade biology class Maggie is expected to dissect a worm. She recoils from the assignment. Even though she loves the class, as well as the teacher – Mr. O. – there is simply no way Maggie “could kill a living thing and cut it up into tiny pieces.”

“What happens,” another student asks Mr. O., “if you refuse to do the dissection because you think dissections are immoral?”

At this question, Mr. O.’s otherwise jovial manner quickly gives way to a stern warning. “Anyone who does not complete a required lab assignment for any reason,” he replies,” receives an F for that assignment.”

When Maggie tells her mother about the predicament she faces, her mother recommends just closing her eyes and holding her nose – “Like changing a poopy diaper.” But the advice doesn’t help Maggie.

The next week Maggie has an argument about the morality of killing animals with her lab partner, Matt. When Maggie expresses her abhorrence at killing a living thing “just to see what it looks like inside,” Matt has a ready reply. “It’s called science,” he says; “it’s probably the reason you’re alive today, instead of dead from smallpox, or TB, or a strep infection.”

When the day for worm dissection arrives, Maggie refuses to participate. “Killing is wrong,” she announces to Mr. O., who promptly sends her to the library. To Maggie’s surprise, she is joined in her revolt by Jake, a classmate of much more radical sentiments than hers, with whom she then establishes an exciting but uneasy relationship.

In Maggie’s English class the teacher announces a competition for the best opinion essay- the winning essay to be published in the school newspaper. As the teacher explains, essays will be judged on how well they respond to objections to the writer’s own expressed opinion. Maggie resolves to write on the treatment of animals.

Two weeks later the biology class is scheduled to do a fish dissection. Since Maggie is one of the best students in the class Mr. O. offers to make a special arrangement for her to watch the fish dissection, without actually participating. Maggie refuses.

The plot thickens. Jake, as it turns out, is in rebellion, not only against Mr. O., but also against the school and the society. Before the book ends, he has gotten both himself and Maggie into serious trouble.

Matt, who had begun the story as the voice of conventional rationality, re-examines his assumptions. He comes to appreciate Maggie’s courage and honesty and takes steps to expose an injustice against her when her opinion essay is unfairly eliminated from the competition.

Alycia, Maggie’s best friend, although she shares many of Maggie’s sentiments, proves to be too spineless to act on those sentiments. And Mr. O. is so much the familiarly avuncular science teacher we all remember from our own school days that we can neither sentimentalize him entirely nor completely dismiss him.

This story is amazingly gripping. I myself found it hard to put down. The characters are compelling and the issues they discuss are as immediately engaging. This exchange is typical:

“What about plants?” Matt asked.

The question seemed to come out of nowhere. “What about them?”…

“If you won’t kill animals because they’re alive, why do you kill plants? They’re just as alive as animals.”

“Not just as alive.”

“Just as alive. You’re either alive, or you’re not. Plants are as alive as you can get.”

“But … ” [Maggie reflects.] Why did Maggie refuse to kill plants? Well, for one thing, if she didn’t eat plants, what would she eat? Even tofu was made out of some kind of plant-what kind, Maggie couldn’t begin to imagine. And it didn’t seem wrong to eat plants. It didn’t. But there had to be more to it than that. Maggie tried to think harder. (75-76)

After thinking about it, Maggie decides the significant difference between plants and animals must be that plants don’t feel anything. But then Matt asks, astutely, “What’s so special about feeling?”

“Well,” Maggie replies gamely, “if you don’t feel any thing-like, if you’re a rock-then it doesn’t matter what happens to you.” (76)

Having retracted her claim that no living thing should killed unnecessarily, Maggie now needs, a couple of pages later, to defend her claim that feelings are the ethically crucial feature, given the fact that Maggie eats eggs and doesn’t worry about the factory-farm conditions under which the chickens live that lay the eggs she eats.

Standing Up to Mr. O. would make a great text to introduce a discussion of moral issues concerning the treatment of animals. Almost all the points one would want to include in such a discussion are raised here and they appear in a way that makes them immediately accessible both to teenagers and to their parents and teachers.