Gareth B. Matthews

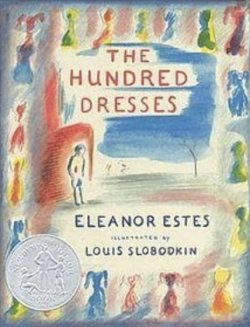

Review of The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes (New York: Harcourt, 1944). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 16(3): 3.

Wanda Petronski was a poor Polish girl who lived with her father and brother in the very poorest part of town; she had only one dress to wear to school. One day, on their way to Wanda’s school, the girls from Room 13 congregated on a street comer to admire Cecile’s new crimson dress. Other girls described their own new dresses.

Silently, Wanda joined the group. Finally she said some thing very softly to Peggy, who wasn’t sure she had heard what Wanda said. When asked to repeat what she had said, Wanda announced, firmly, “I got a hundred dresses [at] home.”

“Hey, kids!” Peggy yelled; “this girl’s got a hundred dresses.”

“Where are they?” someone asked. “In my closet” Wanda replied.

“Oh, you don’t wear them to school,” someone else commented.

“No, for parties,” was the reply.

“Why don’t you wear them to school?” somebody asked. “Perhaps she is worried about getting ink or chalk on them,” one girl suggested derisively.

And so began a teasing game about Wanda’s one hundred dresses. Every school day thereafter Wanda would get teased about her hundred dresses. “Wanda,” one of the girls would say, giving a friend a nudge, “tell us how many dresses you have hanging up in your closet.”

“A hundred,” Wanda would reply.

“What are they like?” someone would ask. And Wanda would describe silk dresses and velvet ones, dresses of all different colors and styles.

Maddie, whose family was also poor, though not as poor as Wanda’s, began to become uneasy about this teasing game. No doubt she began to think it was unkind. But she was afraid to do anything to stop it because she feared that doing so would leave her vulnerable to being teased in a similar way. After all, her circumstances were also modest, even if not so modest as Wanda’s.

Maddie’s discomfort turned to genuine remorse when the class was informed that Wanda and her family had moved out of town. The children learned from a letter Wanda’s father had written to the teacher that he hoped Wanda would not be teased anymore for being a poor Polish immigrant when they got to the big city they were moving to.

Maddie and Peggy went to Wanda’s home in an effort to apologize, but they learned that the family had already moved away. In a surprise development it turned out that Wanda had won an award in absentia. With a new respect for Wanda and with regret for having teased her so mercilessly the class then sent Wanda a letter of apology and the story ends with an intriguing gesture of reconciliation.

Moral education has often been the motive for writing children’s stories. The stories of Hans Christian Andersen and the Struwelpeter rhymes of Heinrich Hoffman certainly have this sort of motivation. But they strike us today as overly moralistic. We feel more comfortable with the zany humor of Theodor Geisel, alias Dr. Seuss, which promotes moral reflection without being moralistic.

There is certainly nothing humorous, or zany, about The Hundred Dresses. Yet the story engages the reader, or hearer, so directly and honestly that it, too, avoids the trap of being merely moralistic. While we are never in doubt that this is a moral tale, the story is so well told that we are immediately captivated.

Specialists in moral education have not agreed on how to think about what moral development really is. Is it the development of the moral feelings – feelings of sympathy, empathy, or perhaps a sense of justice? Or is the development of an ability to reason one’s way through moral dilemmas and conceive general moral principles to govern one’s behavior what is most important?

Whatever we end up with as our best account of moral development, we should make a prominent place in that ac count for the moral imagination. Having a developed moral imagination is not just having certain moral feelings, or having the right principles. It also requires exercising an ability to think oneself into the lives of others, including people with very different life experience from one’s own. One of the very best ways to develop one’s moral imagination is to read good literature and reflect on it.

Our classrooms have never been as diverse as they are today. There are, no doubt, many directly helpful ways of encouraging school children and their parents and teachers to think about what it is like to be racially, ethnically, or socially different from the dominant group in school, and how and why that difference might matter. But one important and helpful thing to do to develop the moral imagination is to read aloud, think about, and discuss together, The Hundred Dresses.