Gareth B. Matthews

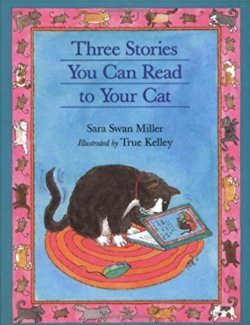

Review of Three Stories You Can Read to Your Cat by Sara Swan Miller (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 16(4): 3.

Your friend went out the front door saying, “I’m going out, Kitty. Now be good. Don’t do anything bad while I am gone.” In a picture we can see a little bit of “your friend” as she went out the door.

“Why would I want to do anything bad?” you asked yourself. “Bad things are not good.” Your friend was being silly.

You looked around the room for something good to do. You spotted the curtain. “Climbing is always fun,” you said to yourself. “And fun is good!” You stuck out your strong claws and began to climb the curtain. In fact, you kept climbing the curtain until it was in shreds.

“Hmmm,” you said to yourself. “There are too many holes in this curtain now. But it was very good while it lasted!”

Your adventures continued. You spotted a plant on the windowsill. You nibbled a leaf and found that it tasted very good. So you nibbled all the green tips.

You turned your attention to the rug. “Cleaning my claws is always a good thing to do,” you said to yourself. You sank your claws into the rug. You clawed and clawed the rug until it began to look shabby.

“Ah,” you said to yourself. “That was very, very, very good.”

Next you knocked a bowl off the table. It shattered into tiny pieces. Then you prowled around the kitchen and smelled the garbage can. You knocked the lid off and burrowed into the garbage in search of what was making such a good smell. You dug all the way to the bottom. The source of the smell was a wonderful piece of chicken.

“Mmmmm,” you said as you munched and crunched the chicken, “That was the best thing I have done all day!”

Doing all those good things made you very sleepy. You crept back into the living room, jumped onto the couch, and curled yourself into a ball. “What a good day I have had today!” you said to yourself. “My friend will be happy. I did not do one bad thing!”

You went to sleep.

This story, “The Good Day,” is the third of the “Three Stories You Can Read Your Cat.” I recently read and discussed it with a group of four and five-year-olds. I wanted to learn something about their ability to cope with philosophical irony. In my discussion with these young kids, Julian, aged four, smiled broadly as he said, “The cat did bad things, [but] he thought that it was good.”

Henry, also four, added, “And it was a mess.” “Did [the cat] think the mess was good?” I asked.

“Yes,” replied Henry; “the cat didn’t know he did bad things.”

The interpretation of the story that these children came up with is a good one, but it is not our only option. One could understand the cat’s antics as “revenge behavior” – getting back at his “friend” for leaving him alone. Then the cat’s saying that destroying curtains or turning over the garbage can was “good,” even “very good,” would count as sarcasm. As it turns out, however, supposing that the cat is sincere in calling what he does “good” makes the story philosophically more interesting.

Ellen Winner, in her book, The Point of Words (Harvard, 1988), maintains that preschoolers are unable to understand irony, particularly the irony of sarcasm. Whether or not Winner is right about children and sarcasm, the preschoolers to whom I read the cat story showed by the grins on their faces, and the acuity of their comments, that they can appreciate philosophical irony. Thus they realized that what the cat did was, according to the cat, good, even though we, the audience, know that it was bad. What makes the discrepancy between the cat’s judgment and our own judgment philosophical is the problematic nature of what is required for something to be good.

In some respects such philosophical irony is like dramatic irony, where the audience knows something the character on stage does not know. What makes irony in a play dramatic is the fateful consequence of the character’s ignorance. What makes the cat’s ignorance philosophical is the stimulus it provides for us to try to clarify, perhaps in discussion, the difficult question of what makes an action good or bad.