Maughn McKay Rollins Gregory

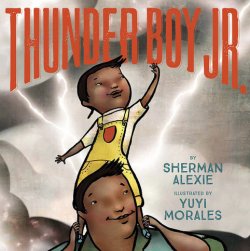

Review of Thunder Boy Jr. by Sherman Alexie (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2016).

When I was a few weeks old, I was rocked in a cradle formed of the right hands of my father, my grandfathers, a few uncles, and the bishop of our Mormon ward. Standing in a circle in front of the congregation in dark Sunday suits, they lifted me slightly up and down while my father pronounced the ritual prayer that named me, introduced me to the community, and petitioned for divine help and guidance for my life.

Growing up on the same street as my father’s parents and the family of his older sister, I understood that my family name came with expectations of respectability, and that my behavior reflected on my extended family. On top of that, my middle name was my father’s first name, which was given alike to my brothers. My first name was taken from a close friend of my parents, with the hope I might develop some of his best qualities. It’s a name most people never heard of, that brought a fair amount of teasing when I was young, and that I’ve been spelling and explaining most of my life.

All three of the names given to me were given with loving deliberation and aspiration. But, of course, I chose neither the names nor the meanings they carried. In the course of my life I have, instead, grown into my names, changed what they stood for (in part), tried on nicknames, and adopted a new name to share with the new family I helped to create. None of that was easy and all of it was important. It’s important to me to say that I finally, fully inhabit all of my names.

The uplift and the burden of a name given but not chosen are keenly felt by Thunder Boy Smith Jr., the young protagonist of this thought- and emotion-provoking book by Sherman Alexie (author) and Yuyi Morales (artist). Like most children at one time or another, Thunder Boy welcomes some aspects of the identity his name imposes on him and chafes against others. No doubt, he speaks for many of our younger selves, at least some of the time, when he shouts: “I HATE MY NAME!” But unlike many of us, at any age, Thunder Boy reflects on his problem with a remarkable degree of self-knowledge and self-possession. And each of the reasons he gives for wanting a different name offers a moment for philosophical reflection.

Thunder Boy’s mother, Agnes, and his sister, Lillian, have “normal” names. His mother wanted to name him Sam. “Sam is a good name. Sam is a normal name,” he remarks. “Thunder Boy Jr. is not even close to normal.” Another issue with Thunder Boy’s name is one I had only partially, but that his creator, Sherman Alexie had in full: “I am named after my dad. He is Thunder Boy Smith Sr., and I am Thunder Boy Smith Jr.” One problem this raises is that people call his father “Big Thunder” and call him “Little Thunder” (another name given but not chosen). As he sees it, his father’s nickname “is a storm filling up the sky,” while his nickname “makes me sound like a burp or a fart.” The bigger problem being named after his father presents for Thunder Boy Jr. is that it obscures his identity. “Don’t get me wrong,” he explains, “My dad is awesome. But I don’t want to have the same name as him. I want my own name. I want a name that sounds like me.”

The Native American nation to which Thunder Boy’s family belongs is not identified, but he draws on its naming tradition in proclaiming,

- I once touched a wild orca on the nose, so maybe my name should be Not Afraid of Ten Thousand Teeth.[…]

- I learned to ride a bike when I was three, so maybe my name should be Gravity’s Best Friend.[…]

- I love powwow dancing. I’m a grass dancer. So maybe my name should be Drums, Drums, and More Drums!

Inventing new names for oneself or for others can be a fascinating philosophical exercise. And in fact, as many of us can relate, people often change their names for different phases of their lives. How long should a name last?

Apart from our names, there is always the problem of how to work out an identity that is personal, a life that has purpose in some ways unique and distinguishable from our family. This quest for identity can become a crisis—for teenagers leaving home, children with many siblings, children of parents with outsize accomplishments or personalities, and children (like me) whose personalities or desires distinguish them as queer in their families or communities. Can I follow the ways of my family and still be myself? Am I obligated to continue family or (minority) community traditions into the future? What if being myself puts me at odds with my family or community? Thunder Boy Jr. speaks for me when he says, “I love my dad but I don’t want to be exactly like him. I love my dad but I want to be mostly myself.” The way that dilemma is resolved in this story is emotionally moving and philosophically profound, even as it leaves the deep questions raised in the story open for reflection.