While the patriot victory in the Revolutionary War was a triumph for American liberty, African Americans in New Jersey were largely denied access to the fruits of independence. James Gigantino (2015:65) in fact argues that “the Revolution helped entrench slavery deeper in in New Jersey and served as a bulwark against freedom.” The causes of this entrenchment were many. For one, as the site of multiple battles, raids, encampments, and troop movements, New Jersey was in disarray by the end of the war. Local communities across the state faced a great deal of work in order to rebuild their farms, towns, and ways of life. This meant that concern with justice for the enslaved was not a top priority for most whites. Second, a white labor force in New Jersey required for this rebuilding was relatively sparse, so enslaved laborers were seen as essential. Third, given that many enslaved Africans self-emancipated during the war as well as fought with the Loyalists against the patriots, there was not a lot of support for them after the war ended. Finally, given that the Quakers remained neutral during the war, most patriots felt little kinship with them. So, their postwar advocacy for abolition did not find much in the way of broad popular support, in fact some blamed Quakers for “poisoning the minds of our slaves” (in Hodges 1999:163).

Debating abolition and slavery

These factors actually came together to revive the schism between East and West Jersey. West Jersey had a larger Quaker population, which included a number of members the very active Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Furthermore, the intensity of battles and the number of African people fighting with loyalists was much less in West Jersey. Similarly, while both regions were overwhelmingly white in 1790, the population of West Jersey had less than half the number of slaves as East Jersey and only slightly more than half the number of people of color. Given that the overall population of East Jersey was one-third smaller than West Jersey, this means that slaves made up 11% of the total population of East Jersey while they only made up 3% of the population in West Jersey. The influence of Quaker abolitionism is also seen in these figures in the case that West Jersey counties had almost twice the number of free people of color than in the East (see population tables in Appendix A). Exemplifying the latter are the 75 of manumissions in Burlington County between 1786 and 1800, which led to a decline by 17% of all slaves in the county. Neighboring counties (Gloucester and Cumberland) also saw a significant decline in number of slaves after 1790, while the slave population in East Jersey counties grew between 20 and 30 percent (Gigantino 2015:74).

The commitment to slavery in the East is recorded in several different sources. Tax Ratable records show that there were 88 different Newark slaveowners in 1783. Advertisements for the sale of slaves also continued. Gigantino (2015:69) records that there were 201 different sales between 1784 and 1804. These sales also show that slavery persisted even as new sorts of work developed. In particular, advertisements reflect a growing demand in the post-Revolutionary era for domestic and industrial work in addition to agricultural labor. The iron industry in the New Jersey Highlands was one place slaves worked as well as a salt works in East Jersey.

Despite sectional differences, West Jersey Quakers continued to push for statewide abolition. They had some success in 1786 when the State legislature passed Quaker State Senator Cooper’s “An ACT to prevent the Importation of Slaves into the State of New-Jersey, and to authorize the Manumission of them under certain Restrictions, and to prevent the Abuse of Slaves” (see Appendix B). The Act ended the sale of slaves in New Jersey brought from Africa since 1776. It also simplified the manumission process and removed from the £200 surety bond attached to manumissions in 1713 for slaves over 35 years of age and established an expectation of “humane” treatment of slaves (Moss 1950:302). The success of the bill appears to have rested on the addition of several new restrictions applied to free African Americans in the state: “Any free black convicted of a crime above petty larceny would be banished from the state. Travel outside the black’s home county was prohibited without a certificate authenticating the bearer’s freedom. Moreover, free blacks from outside of New Jersey were denied entry into the state” (Hodges 1997:115).

That same year, 1786, several West Jersey Quakers formally established the New Jersey Society for the Abolition of Slavery in Trenton (Hodges 1997:115; Fishman [1997:134] notes that the statewide organization did not form until 1793). Two years later, members of this organization lobbied for amendment to the 1786 Act that required stricter penalties for foreign slave trading and the kidnapping of free blacks by slave catchers. Sale of slaves out of the state also required their consent and slaveowners were to be fined if they did not teach their slaves to read. The latter was likely an attempt to improve the capabilities of African Americans as free people in the future. However, as Hodges (1997:116) notes, the law “proved ineffectual in Monmouth County were literacy rates and evidence for schools for blacks are recorded on from 1817.”

West Jersey Quakers continued to fight for abolition in the legislature throughout the 1790s. Bills were put forward in 1790, 1792, and 1794, though none passed, facing fierce opposition from representatives from slaveholding counties like Bergen, Somerset, and Monmouth. These bills proposed a gradual manumission process in which children born to enslaved mothers would be free but required to serve their mother’s master for twenty-eight years. Finally, in 1797, a small minority was able to pass a preliminary emancipation act which indeed children of enslaved mother would be born free, allowing their owner agreed to it. Like in 1786, several restrictions were added to the bill so that it would pass. These included “employment without consent of the Master was prohibited; travel after dark or on Sunday was forbidden to slaves, and minimum rewards were established for the return for violators; public whipping were mandated for minor slave offences” (Hodges 1997:125). Additional changes were made to the slave code in 1798, which, though lightening some of the punishments and restrictions, nevertheless confirmed the state’s commitment to slavery as a whole (see Appendix B).

Alongside their work in the legislature, members of the Abolition Society also supported African Americans seeking to confirm their freedom in the state’s courts. The case of Frank, Cloe, and their son Benjamin in Middlesex County is one example. Frank, a free man, contracted with Cloe’s owner Isaac Anderson in 1778 to purchase her freedom for 180 pounds. As free people, they had a child named Benjamin. The couple later separated, and, afterwards, in 1803 Cloe became sick and was unable to support herself and Benjamin, so she required public assistance. The overseer of the poor then charged Isaac Anderson for their care. After Cloe died, Anderson continued to be charged for Benjamin’s care, at which point he declared that Benjamin was his slave. The Abolition society sued Anderson and successfully won Benjamin’s freedom in court, though Anderson demanded to be paid $150 for expenses related to caring for Benjamin. The Society paid this fee (Gigantino 2015:78).

Society members supported other claims like this as well as in support of kidnapped free blacks being transported south. Four free African Americans were taken from debtor’s prison on Martha’s Vineyard in 1803 and stowed aboard the sloop Nancy. The captain intended to take them south to be sold as slaves. While docked in Egg Harbor, the four captives escaped and found protection among abolitionists who enlisted the Society to provide their legal protection (in Gigantino 2015:78).

Gigantino (2015:81) notes that despite these acts, most Abolitionist Society members were ambivalent about effort to support black equality. “In 1796 the society forced its Gloucester chapter to recall funds earmarked to educate black children.” Their legislative failures and compromises also reflect the fact that their focus “was the legal institution of slavery instead of improving black life.”

Intensification of racism

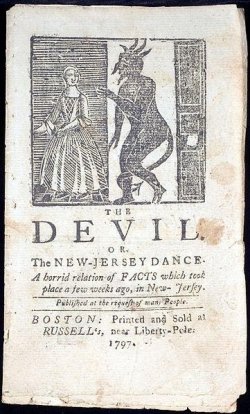

Part of the failure to see the humanity and struggle of Africans American—enslaved and free—can be attributed to an emerging racist discourse among whites which suggested and depicted African Americans as a separate and inferior race incapable of succeeding in freedom. Evidence in New Jersey for this ideology is found in reprints of Edward Long’s History of Jamaica which suggested enslaved Africans were violent savages or in Almanacs that “continually portrayed Africans as heathens or devilish apes” (in Gigantino 2015:69). In 1797 a pamphlet was printed The Devil or the New Jersey Dance: A Horrid Relation of Facts which Took Place a Few Weeks Ago, in New-Jersey. Published at the Request of Many People, that told the story of a murderous black fiddler.

Religious leaders also added to this racist image. John Nelson Abeel, a Dutch Reformed Minister inspired fear by suggest that if the slaves were freed that whites would suffer from “negroes who are black as the devil and have noses as flat as baboons with great thick lips and wool on their head [along with] the Indians who they say eat human flesh and burn men alive and the Hottentots who love stinking flesh” (in Gigantino 2015:70).

In 1794, as an agent for “Dutch investors and owners of vast land tracts”, Theophile Cazenove advanced this racist rhetoric in his published travel journal. His opinion of free blacks was especially low: “the free negroes are quarrelsome, intemperate, lazy and dishonest. Their children are still worse, without restraint or education. You do not see one out of hundred that makes good use of his freedom or that can make a comfortable living, own a cow or a horse …. They are worse off than when they were slaves” (in Fishman 1997:144). Fishman also notes that “is strictures about African Americans not owning land or livestock did not show knowledge of the legal disqualifications in New Jersey history [preventing] African Americans form doing this.”

Slavery expands in East Jersey

As West Jersey Quakers sought to end slavery, those in East Jersey invested in the practice further. Between 1790 and 1800, the number of slaves in East Jersey counties grew from 8,196 to 9,406. If we include Morris and Sussex Counties, which were both closely connected to East Jersey and also saw their slave population grow during this decade, this figure rises to 10,695 or 86% of the statewide total.

East Jersey slaveholders also controlled of the majority of wealth in the state. In one example from Monmouth County, “slaveholders in Middletown, Upper Freehold, and Shrewsbury between 1784 and 1808 possess more than five time the average amount of land, four times, the number of cattle, and five times the number of horses as freedholders without bondspeople”(Hodges 1997:118). Similarly, in Bergen County, slaveholders in “Hackensack, Bergen, Harrington, and New Barbados … owned for times as many horses and cattle and non-slaveowners” (Hodges 1999:165). Large holdings by slaveowners left very little property for other free people, both black and white, a factor that led to a scarcity of young white male laborers who left slaveholding counties and the state altogether for opportunities elsewhere. Hodges (1997:118-19) concludes that “enslaved blacks, then, were the species of property that best insured prosperity, maintained larger farms, and provided the means of mobility.”

The control of this wealth is featured in the records of wills in the state. Only one of twenty-two will probates in Monmouth County between 1782 and 1784 freed a slave. The rest bequeathed their chattel property to relatives (Hodges 1997:122). Notably, Quaker influence can be seen, especially after 1790 in Monmouth County, “when twenty-five of ninety-seven slave-owners’ wills provided for emancipation” (Hodges 1997:127). All but one of these emancipations was gradual, in the sense that the slave would remain the property of a widow or child for many years following the master’s death. In Middlesex County, for example, William Stone declared in his 1788 will that his slave “Cato was to be free when he reached the age of thirty” (Hodges 1999:173).

A testament to the wealth attached to slave ownership in New Jersey is recounted in the recent book edited by Marisa Fuentes and Deborah White, Scarlet and Black: Slavery and Dispossession in Rutgers History. Throughout this book, researchers present clear data that associates the founders of the New Jersey’s state university with slavery. One major benefactor and trustee from 1787 until 1815 was Dutch minister Elias Van Bunschooten, whose family’s wealth derived in no small part from enslaved labor. The family bible, which records more than 59 slave births, was summarized by a biographer this way:

Of those slaves whose names are recorded in the old Dutch family bible, we know twelve sprung from the loins of the Nanna family, five from Cetty, fourteen from the tribe of Cay, twelve from the Ginna, twelve from Susanna, four from Betty, and others from Tudd, Ezebel and Robe Hear-man Judge. The dates of births recorded range from July 30, 1749, when Susanna Betty was born, onwards through a succession of primitive names such as Nanna, Ginna, Cay Betty, Betty Susanna, Pegga Susanna, Caty Suanna, Eve Ginna, Robe Susanna, Nanna Betty, Adam Susanna, Cay Robe and many others, until the even century is reached when more common names appear, such as Silver in 1801, Simon in 1802, Dorcas in 1804, Ruth 1806, Alfred 1807 and Henry 1810 (in Boyd, Carey, and Blakely 2016:55).

Violence against the enslaved

The preservation of wealth through slave ownership and inheritance certainly established a class of people with a vested interest in the continuation of slavery in the state, yet wealth alone could not suppress either white racial violence or black resistance. Hodges (1997:134) recounts the story of one slave, Sambo, whose petty thefts led his master to eventually break his will. “The Formans considered Sambo exemplary, a servant ‘who stayed close to home, was very submissive.’ These qualities, David Forman, reported, ‘exalted our compassion,’ to ‘let him have a little liberty like all the rest of the Negroes in the county we permitted him to go out for an evening.’ Left to his own designs, Sambo immediately stole two geese and took them ‘to an Old Free Negroe here.’ Their compassion now abased, the Formams gave Sambo 100 lashes.” After additional lashings for similar small offenses, Forman reported that “Sambo became more malleable.”

Even as gradual emancipation was being codified, white violence persisted. “In Bergen County, in the early nineteenth century, slaves were still being shipped by master and governmental authorities. Records were being kept as to the number of lashes administered. For example, in 1804, … the ‘Slave of John Dennis (in New Brunswick) was whipped two days. The first he had 40 striped & and the other 30” (in Fishman 1997:124). Similarly, in 1801, Ned and Pero, “were found guilty in Bergen of larceny and ordered to be whipped from place to place throughout the county during the course of a month. Each week they were whipped at a new location: the courthouse, Pond’s Church, Hoppertown, and New Bridge, for a total of 400 lashes. Ned died from his whippings” (Hodges 1999:180).

Fighting to acquire and preserve their freedom

Fighting for their freedom, especially among those already legally free, was the preoccupation of New Jersey’s African Americans during this time. The threats to their freedom came in various forms, but in most cases, it involved false claims of ownership of free people by whites. For example, Phillis, who had been free from 1785 to 1795 was seized by “one McDonald … under a bill of sale from Hanns, son of Phillis’ former owner. The son would not honor his mother’s promise to set Phillis free” (Fishman 1997:127). The State Supreme Court heard the case and set her free. Another example is the case of Cuff in Somerset County. Cuff was promised his freedom by his master Gilbert Randolph, “either at his own death or when his son, James, came of age. However, when James came of age, Randolph reneged on the agreement and demanded additional years of service.” Again, the court found in favor of Cuff and set him free (Gigantino 2015:80).

Another way to gain freedom was through private contracts between slaves and masters that stipulated the terms of service. The slave Lewis was

sold to New Jersey Chief Justice David Brearly on April 28, 1780 with the contractual provision that ‘said Negro is to become free after thirteen years.’ When Brearly died eleven years later, his executors gave Lewis a pass stating he had ‘two years and seven months to serve [and] (as he not wanted by the family) has the Liberty to travel for a few day Not exceeding thirty miles from this Place to find master of his own choice.’ Lewis made an agreement with merchant Moore Furman of Trenton, who paid Brearly’s executors 18 pounds, 15 shillings for the remainder of his time (Hodges 1997:128-29).

Many enslaved persons also found freedom by escaping their bondage. In just two years after the end of the Revolutionary War in Monmouth County alone twelve slaves ran away. Hendrick Smock’s slave Ben ran away in 1784. He ‘spoke very well … very likely will change his name and pass for a free man” (in Hodges 1997:122-23). Fishman (1997:128, 139) reports that “at least eighty-nine slaves fled from, to, or within New Jersey” between 1784 and 1792, and another “sixty-seven Black runaways from the period 1801-1806” in central Jersey, and finally, “forty-six Black runaways for the period 1807-1815” in northern New Jersey. A notable trend observed by Hodges (1999:174) is that “nearly third of the 1,232 self-emancipated people of color enumerated [for New York and New Jersey] … took flight between 1796 and 1800.” The point here that this rash of self-emancipations certainly played role in the passing of state-wide manumission legislation in both states at that time.

One ill effect of the absconding slaves was the way whites reacted such that any person of color could be seen as a possible runaway. Sam and Tom two free African Americans narrowly escaped re-enslavement when they were captured as possible runaways in 1785. They were jailed but set free after they produced certificates of their freedom. Fishman (1997:128) rightly asks: “what if they did not have a certificate at hand?” In 1797, a traveler in Elizabethtown noted that the jail there was used almost entirely to hold escaped slaves who were held a certain number of days before being sold. This could very well have happened to free blacks who could not prove their status.

African American resistance

Other forms of resistance practiced by enslaved African Americans during this era included petty crime, burglary, assault, and arson. In Monmouth County, black people are known to have stolen linen, horses, and sheep, for which they received thirty-nine lashes. In Bergen County, black men assaulted white men on at least three separate occasions between 1793 and 1795. “’Negro Jude’ was arrested in 1792 for intent to burn the house of Roeloff Van der Veer of Freehold” Monmouth County (Hodges 1997:133). Cases against Bet (1780) and Cuffe (1794) in Bergen County also involved arson (Hodges 1997:144, n.34). Fishman (1997:129) notes that in 1788 “three African Americans were executed in Middlesex County on the ground of concerted arson activity over a period of ten years.” Six fires were recorded in Elizabethtown in 1797 were blamed on a slave conspiracy as were fires in Newark. In the 1790s, there was a rash of fires up and down the East Coast, including in New Jersey. These certainly worried whites and alongside the increase in self-emancipations, spurred their action on the manumission legislation.

The presumption of slavery

Despite resistance and the push for freedom from both white and black communities, free people of color in New Jersey remained a perceived threat to the social order. One example comes out of Newark in Essex County. Being a port city, Newark had more opportunities for work and independence than the countryside, so it was place free African Americans were drawn to. Yet, in 1801 the white residents of Newark convened to discuss their concerns about the newcomers. “The proposed agenda included the following points: (1) the ‘unlawful residence’ of free Black people in Newark, (2) meetings of the free Black people, (3) the ‘unlawful absence of slaves,’ [and] (4) unlawful dealings with or employment of slaves” (in Fishman 1997:132). City residents called another meeting eight years later to again address the “’threat’ of the increase in the number of Free African Americans … It projected vigilante action: ‘concerted means … to suppress riotous and disorderly meeting of Negroes in the streets at night’” (Fishman 1997:162).

During the decades after the Revolutionary War, African Americans were burdened with a “presumption of slavery.” Nothing about the way of life in New Jersey, even active abolitionist efforts, had undone the association of blackness with bondage. Free African Americans thus were required to demonstrate their freedom to anyone who asked and faced the threat of defending if not losing their freedom at any point if accused of crime, escape, or because of the legislative will of the state’s leaders. “It was not until 1836 … that the New Jersey Courts abandoned their position that a person of color was presumed to be a slave unless evidence to the contrary was provided” (Fishman 1997:142).

African American landownership and communities

Despite these troubling conditions, some African Americans were able to develop financial security and social standing in the years after the Revolution. One of the bases for success, of course, was owning property, and during this era the foundations for a handful of free black communities were laid. One these is known as Skunk Hollow, which was a community of about 75 individuals living near the NJ-NY border in what is now Palisades Interstate Park. Skunk Hollow was founded by Jack Earnest in 1806. By 1880 the community grew to 75 people living in 13 households, after which it declined and was altogether gone by 1910. Archaeologist Joan Geismar completed a very thorough study of Skunk Hollow, which she published as The Archaeology of Social Disintegration in Skunk Hollow: A Nineteenth-Century Rural Black Community (Geismar 1982). Other free black communities formed in Monmouth, Middlesex and in south New Jersey, where one, Tumbuctoo Westhampton, NJ, in Burlington County has been examined archaeologically (Barton and Orr 2015, Hodges 2019:50).

Prior to the formation of free black towns and communities, there are records that show black land and property ownership as early as 1784. Sixteen free blacks in Middletown and seventeen free blacks in Shrewsbury were listed as farmers in Monmouth Country in 1784 and 1787. These included Tom Cavey and Ephraim Rawley who owned seventy-five acres of land and Samuel Lawrence who owned 100 acres and five cows. Others simply owned cattle, horses, and hogs (Hodges 1997:123).

Probably the wealthiest African American in these years was a man named Mingo, who did not appear to own land, but his other property was valued at £685 in 1802. This included “wearing apparel worth seven pounds, ‘horses, wagon & guns Saddle and bridle’ worth twenty-five pounds, and grain, corn, rice, and ‘cakes of cider in the cellar.’ Most of his estate consisted of £586 of ‘Notes and bonds against sundry people.’” Here we gain not only understanding of the way Mingo acquired his wealth, but also the chance to reflect on exactly how people of color could survive economically in the racist world they lived in. Specifically, Mingo was most certainly a creditor to other African Americans who may have seized this opportunity to secure a foothold in the local economy. One such use of credit would have been to acquire land through leases, of which Caesar Abraham held four at the time of his death (Hodges 1997:131; also see examples in Fishman 1997:152-157).

We are lucky to have a view on these conditions from Brissot de Warville who travelled in New Jersey in 1788. De Warville notes that African American had a higher death rate than whites largely due to “poverty, neglect, and especially the lack of medical care.” He also noted that “African Americans are not loaned money by commercial establishments. They aren’t even allowed to enter those establishments!” (Fishman 1997:149). Still, visiting black farmers he was “impressed by the good clothes, their well-kept log cabins and their many children” (in Hodges 1999:176). De Warville was clear that African American suffering was to be blamed entirely on whites, who acted “as if [black people] belonged to an inferior race” (in Fishman 1997:149).

African American religion

Black communities also found refuge in religion, especially through in their own spiritual leaders and institutions. Most white churches denied African Americans membership, including Quakers who were otherwise their most active supporters. Hodges (1997:138) notes that a fear among Quakers was “once accepted, [they] ‘must be intitled to the privilege of intermarriage.’” The Dutch Reformed Church took another path in 1792 when it declared that “no difference exists between bond and free in the Church of Christ,” yet acting on this liberal sentiment appears to have been confined to the city (in Hodges 1999:181). In the countryside, such as in Freehold in Monmouth County, free blacks were accepted as church members but were expected to sit in segregated “negro pews” (Hodges 1999:182). In lieu of joining white churches, African Americans in the post-Revolutionary era crafted their own religious communities.

Two itinerant African American preachers in particular have been documented to travel and preach in New Jersey. George White, a former slave in Virginia, became “an exhorter in Shrewsbury and Middletown” in Monmouth County in the 1790s. He wrote that “many of my African brethren, who were strangers to religion before, were now brought to close in the offers of mercy’ through trances and shouts” (in Hodges 1997:139). John Jea was another African itinerant preacher who found reception in New Jersey. Jea was born in Nigeria, but he was a slave in New York when he “claimed an angel taught him to read the bible in Dutch and English.” He was baptized in a Presbyterian church, a fact that he claimed set him free. As a preacher Jea drew hundreds of African Americans to his services. “The meetings were based loosely on Presbyterian and Methodist ‘love feasts.’ Jea wrote that the services were held “out of doors in the fields and woods, which we used to call our large chapel” (in Hodges 1997:139) where he preached “a theology of rebirth by linking to story of Lazarus with aspirations of an emerging free black congregation” (Hodges 1999:185).

In addition to black preachers, African Americans also made initial step towards creating their own Christian denominations in this period. The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church was founded by Richard Allen in Philadelphia in 1787. By 1800, there was an AME church in Salem County and in 1807 another in Trenton. By 1860 there were thirty-two AME churches in the state. In New York, dissident African Americans formed the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church in 1796 (Hodges 1999:184). Along with Baptist and other denominations, the black church became a vital institution supporting free African Americans in the nineteenth century.

1804 Gradual Abolition Act

The closing event in this post-Revolutionary Period was the passage of “An act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” on February 15, 1804 (see Appendix B) making New Jersey the last northern state to take a step toward freeing its slaves. This act established that all children born to enslaved mothers after July 4, 1804 would be free once they served their masters for a term “if a male, until the age of twenty-five years; and if a female until the age of twenty-one years.” This calculation was one way to appease slaveowners who feared that setting slaves free would cause great material damages their way of life. Instead, the children of enslaved mothers would be required to labor through some of their most productive years in much the same way as if they remained enslaved.

As many have put it, the 1804 Act did not free any slaves. It also provided nothing to these young men and women upon the completion of their indenture, as was the norm for white servants. In addition, New Jersey, unlike very other state in the North that adopted a gradual emancipation process, never amended the law to free those born before the act went into effect. As such, slavery did not formally end in New Jersey until the 13th amendment to the US Constitution was ratified in 1865.

As the premise of the 1804 Act borrowed from other northern state legislation, its success rested largely on the abandonment system. “Modelled after New York’s law, the abandonment system allowed slaveholders to surrender children born to their slaves to the local overseers of the poor before age one. These children would then be bound out like poor white children until adulthood” (Gigantino 2015:91). Slaveholders would then be paid by the state to care for these children, a process that not only won them over to support the Act, but nearly bankrupted the state in 1807.

This crisis led many to call for a repeal of the law altogether including among Bergen County slaveholders who declared that abolition was “unconstitutional, impolitic, and unjustly severe” (in Hodges 1999:171). Morris and Salem County citizens also lodged their protests. A petition from Salem County complained that

“there is no white laboring population sufficient for the farming interest, and we do seriously believe that the passage of the law will cause so much difficulty that the farmers will not be able to procure workmen for their farms. Your memorialists need only remind your honorable body that the black population is exceedingly ignorant and prejudiced and cannot be expected to yield that regard to the law which is evoked from the white citizens of the state” (Moss 1950:304)

In fact, critics of the Act appeared almost immediately, such as Torrence Demarest among others who claimed that free blacks would “have more security and be better off as slaves” (Fishman 1997:138). In contrast, African Americans embraced the opportunities of presented by the Act, such as Quamino, a former slave in Burlington County, who said in 1806, “I don’t know much about freedom, but I wouldn’t be a slave again if you gave me the best farm in the Jersies” (in Fishman 1997:138).