Assignments and assessments allow students to apply and demonstrate learning relevant to a course learning objective. Assessments, assignments or any task you assign can be individual or collaborative, brief or lengthy, or in any genre or format. Ideally assessments have two functions: they at once further student knowledge and skill through completion and they provide information about learning.

In designing assessments, use your learning objectives as a baseline and then review your assessments for variety, opportunities for feedback, and appropriateness to the student population. Consider these questions:

- How well do the tasks relate to the learning objectives?

- Are the tasks assessable? With criteria that students can understand?

- Are the tasks realistic, tied to the real world?

- Are the tasks varied in their nature, drawing on different learning styles and strengths that students may have?

- Are the tasks well scaffolded – with steps, space for practice, and opportunities for feedback that will support success?

It’s easy to get in the habit of reusing the same assignment again and again. Instead innovate and try new strategies.

Formative assessments help both you and your students measure their development and should be offered frequently. Formative assessments are typically ungraded or low-stakes opportunities to advance and measure student knowledge and skills.

Summative assessments are used for evaluation and are typically assigned at the end of a unit or course.These are tied to a quantitative evaluation and are graded based on a set of criteria and standards. Summative assessments should be forward-looking, authentic, and well connected to the lessons taught.

| Formative Assessments

typically ungraded or low-stakes opportunities to promote and measure student knowledge and skills

|

Summative Assessments

typically comes at the end of a unit/topic or semester, tied to a quantitative evaluation (grade) based on a set of criteria and standards of learning progress. Summative assessments should be forward-looking, authentic, and should the purpose of the learning (applied, real-world, relevant to the student’s path) |

|

| Examples |

|

|

| Characteristics |

|

|

Scaffolding and sequencing are very closely related assignment strategies that offer many benefits to both instructors and students.

These strategies allow instructors to create and better align formative assignments with course goals, objectives, and content. Instructors can facilitate more efficient and engaged learning as they intervene frequently, in turn enabling quicker and more efficient grading. Using these strategies encourages student reflection on learning, learning during the assessment process, and implementation of feedback in “real time.”

The strategies provide students with an excellent “real-world” connection by showing them how professionals in their fields of interest approach and think about larger projects, writing assignments, and other work. They assist students with time-management–breaking assignments into smaller pieces means students cannot leave all the work until the night before! They master new skills or concepts through repetition and are asked to think critically as they are guided through completing discrete, manageable cognitive tasks

| Scaffolding | Sequencing |

|

|

Ideas for Scaffolding Activities

(adapted from Miami University Howe Center for Writing Excellence)

In-class activities*

- Assignment Pre-Write – examination and reflection of assignment prompt

- Brainstorming for topic generation

- Freewriting about possible topic

- Review of resources available

- Reading a journal article together

- Creation of project timeline

- Practice of skills needed in assignment

- Integrating sources workshop

- Research question or thesis statement workshop – students introduce question or thesis to peers

- Grading rubric discussion or generation

- Review/analysis of example assignments

- Peer review of outlines

- Oral draft to share in small groups

- Peer review of written draft

Short Assignments

- Audience/stakeholder analysis

- Research Question or Thesis

- Proposal

- Annotated Bibliography – potential sources

- ¾ Drafts – After completing, students could create and deliver class presentations on their work in-progress, read their paper to a panel of peers, or share a poster about their work to date

Individual Interactions with Instructor

- Assignment “check ins” with questions for instructor

- One-on-one conferences with instructor

- Review proposals

- Provide feedback on drafts or any scaffolded assignment

* Peer-feedback steps can be used after all or any of the above scaffolded and sequenced assignments: students read, watch, or listen to the submissions made by their peers in the above activity and provide feedback while their own submissions are reviewed by their peers.

Example of scaffolded and segmented assignments

Research paper and scaffolded assignments collectively make up 40% of final grade. Choose your own topic and write a 4–6-page research paper.

Research paper assignment prompt: What is a social problem that impacts children and families living in New Jersey. Your paper will follow this format:

- Introduction

- Who the social problem impacts, and what that impact is

- How the field of child advocacy has responded to this social problem

- How the field of child advocacy might more effectively respond to this social problem

- Your personal thoughts on the problem

- Conclusion

Assignments

- Explore and reflect on the assignment prompt – 250-500 words to submit by the end of the class (instructors could choose to use as either an individual and/or group activity) – 5%

- Annotated bibliography – at least 4 scholarly sources – 5%

- Research outline (1-2 pages) – 5%

- 3/4 Draft Presentation- A 5-minute presentation on their work-to-date made by student to class with other students giving feedback – 10%

- Final research paper – 15%

Clarity and consistency in assignments help students do the work more efficiently and effectively. Try OFE’s assignment-design template to ensure you provide the relevant information. Also available as a writable Google Doc template.

Assignment Title

[Title the assignment to indicate task and/or specific relevance to course (e.g., “Reflection Paper #1”)]

Overview / Purpose

[Clearly state the learning objectives of the assignment. What is the purpose and rationale of the task? That is, what will students gain from completing the work in this assignment? Consider both the knowledge and the skills to be acquired, and their relevance on multiple levels – to the class, discipline, university/institution, future careers, etc., and indicate each in the purpose section.]

Task(s)

[Describe in detail the steps required to complete the assignment, including the sequence of tasks and what materials should be used (and may not be used). For larger-scale assignments, this section should be scaffolded into multiple tasks with separate due dates and opportunities for feedback. If appropriate, provide time in the sequence for brainstorming, conceptualizing, drafting, receiving feedback, and making revisions. Consider the rungs of Bloom’s Taxonomy to move from lower-level to higher-level thinking in the assignment. Be careful not to make leaps in cognitive steps; sequence them to avoid confusion.]

Materials

[If not already indicated within the above sections, clearly state which materials students must and must not use in their completion of the assignment. State where such materials may be found (e.g., on reserve at the library). If you require particular kinds of materials, how many must be used and cited?]

Instructor Expectations / Grading Criteria

[Detail what a successful finished product looks like. Avoid “jargon”; describe for example what a response paper or a keystone project is either here or from the outset of the assignment description. Set clear parameters for what constitutes “excellent” versus “unsatisfactory” work. Include in this section multiple samples for students to assess and use as models. Include a clearly-defined grading rubric, if applicable, or a checklist for students to follow. If not included elsewhere, include here the grading scheme of the assignment: is it graded as complete/incomplete, with a letter grade, a percentage, or point grade?]

Requirements

[State the scope required (e.g. how many words or pages; how much time; how many sources, etc.) Allow for multiple means of expression to support different learners. Clearly state how sources are to be cited (e.g., MLA, APA style). Consider including a statement regarding the extent to which AI may be used in the assignment.]

Submission and Due Date

[Indicate what format submissions must take and how they are to be turned in. For example, are PDF documents or Google docs expected? If a video is submitted, what formats are allowed? Are hard copies required or are assignments to be submitted on Canvas.

Due dates may also be incorporated in the task section if the assignment is “chunked” into multiple parts.]

Assignment Strategies

What is an assignment? What purpose does it serve in the teaching and learning relationship? How do your students understand why, and how, and what they should learn about? How can they apply course concepts in ways that contribute to real-world knowledge and academic development? Below are several evidence-based models of classroom instruction and assignment design.

Just-in-Time-Teaching (JiTT) with examples.

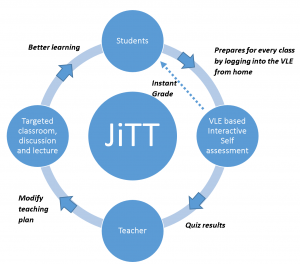

Just-In-Time-Teaching (JiTT) – relates course content to students’ lives, builds curiosity and deepens conceptual knowledge through the in-and-out of class learning process. It is dialogic and intended to replace more traditional passive lectures and instead identify areas student’s need more instruction (bottlenecks) that better inform their understanding and learning. JiTT is a teaching and assignment process that has students complete preparatory assignments prior to class in which they read, review, or do something and then answer related questions. These “warm-ups” act as a communication tool between students and their instructors, creating a feedback loop that allows instructors to modify or adapt their in-class activities and instruction that addresses learning gaps visible through the out-of-class assignments. In JiTT, student-generated responses make the learning process visible and inform in-class activities and discussion.

- Just-in-Time-Teaching cycle.

Designing effective JiTT questions. Effective questions vary from discipline to discipline and instructor to instructor, but have common characteristics that make them effective for fostering deeper learning and engagement from students. They:

-

- yield a rich set of student responses for classroom discussion (including addressing myths, misconceptions, or biases).

- encourage students to examine prior knowledge and experience.

- require an answer that cannot be easily looked up.

- require that students formulate a response, including the underlying concepts, in their own words.

- contain enough ambiguity to require students to supply some additional information not explicitly given in the question.

Examples from across the disciplines.

- Examples from STEM disciplines available at Carleton.

- Just-in-Time-Teaching example questions (Google Books link, pages 8-9)

Source: Simkins, S. & Maier, M. H. (2010). Just-In-Time Teaching: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy. Stylus.

Creating Wicked Assignments.

- Wicked Assignment Design

- This method responds to problems with traditional research assignments such as students’ relying on other sources (the data dump) instead of taking risks by speculating or coming up with their own ideas (risk-aversion, avoiding uncertainty or complexity).

- Students operate from the belief that instructors already know this stuff, that instructors have assigned or presented what they want them to replicate, or that others have already said or researched everything there is to know about this topic.

- A wicked assignment requires students to assume authority by crafting questions that ask “so what?” and calls for judgments, decisions, or meaning making of outside sources. It builds in instructional activities that has students assume authority (as teachers themselves, or by applying these in uncertain context where they have to make decisions

Sample Assignments:

- Biology: “create an informational pamphlet on an emerging infectious disease, pitched to PTO [Parent-Teacher Organization] parents. Include causative agent and vector, threat to local population, and possible measures to reduce risk” (Handstet, 2018, 69)

- Western Civ: You are running Congress. In an address to your potential constituents explain how the political, religious, economic, and social problems of Rome might inform policy in an American context.

- Metaphysical Poetry: You have been invited to lecture to two separate audiences on John Donne. You are asked to deliver a sermon to a Christian congregation (you can specify an exact one if you wish) on spiritual principles in John Donne’s poetry. Then the next day you address a local atheist group on John Donne’s religious poetry. Provide a close reading of least one poem and draw upon relevant sources in our reading.

- Nutrition: The New York state government has created a council to develop a list of recommendations regarding the lifestyles of primary school age children. As the nutritionist on the council, your job is to choose a region, examine its population, and construct an appropriate menu for breakfast, providing a carefully researched rationale that takes into consideration all the relevant components of our work this semester.

Source: Handstet, P. (2018). Creating wicked students: Sesigning courses for a complex world. Stylus.

Assignment Design Using Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy provides a useful framework for thinking about the level of assignments you develop as well as how to construct them clearly.

- Handout of Bloom’s Critical Thinking Cue Questions for designing assignment prompts and questions (opens as PDF).

- Simple example using the children’s story of Goldilocks:

- Assignment Design Template using Bloom’s Taxonomy with examples from across disciplines (opens as editable DOCX).

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) Assignment Design

- TILT is composed of three sets of factors used in transparent assignment design: purpose, task, criteria

- Purpose of assignment: Define for students what skills are practiced and what knowledge is gained (real world scenarios) from an assignment. How do you discuss these two factors with students before students do any work? How can you answer their questions and make the purpose as transparent as possible? (Youtube on Purpose)

- The Task: Explain what students are expected to do and how – discuss issues of power and choice here. How can students assume authority and take responsibility for their own learning? (Youtube on Tasks)

- Criteria: Offer a checklist or rubric for self-evaluation and annotated examples of excellent examples of the assignment. Have you given them examples or models of good research, what you are looking for as an evaluator? When will they receive feedback (Youtube on the Criteria).

Beyond these three points of assignment design, Winkelmes’ survey results suggest a few fairly easy but important practices that can improve both current and future learning in different disciplines and for different class sizes. The information below comes from her article published in Liberal Education (Spring 2013, Vol. 99:2), “Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning.”

In humanities courses at the introductory undergraduate level, two practices seem to benefit students’ current course learning experiences depending on the size of the class:

- Discuss assignments’ learning goals and design rationale before students begin each assignment (in classes ranging in size from thirty-one to sixty-five students).

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class (in classes ranging in size from sixty-six to three hundred students).

In social science courses at the introductory undergraduate level, particularly in mid-sized level classes (31-65 students) several transparent methods have statistically significant benefits for students’ current course learning experiences:

- Discuss assignments’ learning goals and design rationale before students begin each assignment.

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught.

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class.

In larger introductory courses in the STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), the following transparent methods have statistically significant benefits for students’ current course learning experiences and for their future learning:

- Explicitly connect “how people learn” data with course activities when students struggle at difficult transition points.

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught.

- Discuss assignments’ learning goals before students begin each assignment.

Students at the intermediate and advanced levels in STEM courses (again, larger classes) indicated that the following methods are helpful to their current and future learning:

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught.

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class.

The following practices are associated with increased current learning benefits for students in large-enrollment courses in the Transparency study (ranging from sixty-six to three hundred students in humanities and STEM courses; three hundred or more students in social science courses):

- Discuss assignments’ learning goals and design rationale before students begin each assignment (introductory social sciences).

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught (introductory social sciences, introductory STEM, intermediate and advanced undergraduate STEM).

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class (introductory humanities, introductory social sciences, intermediate and advanced STEM).

The following practices were associated with increased future learning benefits for students in large-enrollment courses:

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught (intermediate and advanced undergraduate STEM).

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class (introductory social sciences, intermediate and advanced undergraduate STEM).

In large enrollment courses where the following transparent methods were used, students responded more positively than students in similar control-group courses (where no transparent methods were employed) to the question, “How much does the instructor value you as a student?”:

- Discuss assignments’ learning goals and design rationale before students begin each assignment (introductory STEM).

- Debrief graded tests and assignments in class (introductory humanities, introductory social sciences, intermediate and advanced undergraduate STEM).

- Gauge students’ understanding during class via peer work on questions that require students to apply concepts you’ve taught (introductory social sciences, introductory STEM, intermediate and advanced undergraduate STEM).

- Explicitly connect “how people learn” data with course activities when students struggle at difficult transition points (introductory STEM).

Authentic assessment evaluates learning in real-world contexts. Often called applied learning, assessments that are authentic aim to be meaningful, practical, and connect course content with real-world problems or tasks.

Grant Wiggins, who first coined the term in 1989 (A True Test), states that an authentic assessment:

- replicates or simulates the contexts in which adults are “tested” in the workplace or in civic or personal life.

- requires judgment and innovation.

- assesses students’ abilities to efficiently and effectively use a repertoire of knowledge and skills to

- negotiate a complex task.

- allows appropriate opportunities to rehearse, practice, consult resources, and get feedback on and refine performances and products. (Indiana University)

One of the best things students can do is reflect on their learning – to see for themselves what it is they know and do not know. Strong learners do this all the time, reflexively, but less experienced learners need guidance in developing their learning muscles.

Many of these reflective exercises fall under the category of “retrieval practice,” which makes use of frequent, low- or no-stakes testing, in which students (and instructors) gain awareness of student learning and retain newly-learned knowledge better. Activity ideas include “brain dumps” or “free recall” exercises where students are prompted to write specifically about recent material learned, and/or take short, ungraded quizzes at the beginning of class meetings to test recall of material. Research suggests this retrieval process aids learners in retaining and mentally organizing information and helping move learners to higher-level understanding of material.

Here are some reflective assignments you can use right in class or as homework:

Problem-solving Log: Students record their steps or thinking in solving a problem or completing an assessment. You can require regular logs (or drafts) with progress reports and steps taken to complete the task. Have students identify challenges, gaps, knowledge they already had, or new knowledge learned.

Exam wrappers: Add a question to your exam to promote metacognitive thinking about the process of exam preparation. Direct students to report and reflect on how they prepared for an assessment and what they imagine doing differently next time. After the exam, or when you meet again next, conduct a short discussion asking students to share their reflections with classmates to support improvement in exam preparation activities. (Ambrose et al., 2010). For an example you can import and adapt for your course, log into Canvas, click on “Commons” (far left navigation) and search “Quiz and Exam Wrapper Survey.”

Short quizzes that test for understanding: A five-minute quiz once a week, perhaps even a one-question quiz, shows students immediately what their level of understanding is. Typically with low point value, short quizzes should be followed by brief discussion of questions missed and investigation of what led to these gaps.

Muddiest point: This technique consists of asking students to jot down a quick response to one question: “What was the muddiest point in [the lecture, discussion, homework assignment, film, etc.]?” The term “muddiest” means “most unclear” or “most confusing” (Angelo et al., 1993), and identifying it essentially helps students discover and zero in on the questions they need to address to conquer a lesson.

Minute papers: These provide an assessment of what students learned in a class, and help students inscribe learning into long-term memory. Minute papers are easy to do. Ask students to write for two minutes about the following questions: “What was the most important thing you learned during this class?” and “What important question remains unanswered?” Collect these papers as students leave for your own learning, returning them to students the next class session. Notes or evaluation or not necessary, though it may be useful to make general comments about what you observed about students’ understanding.

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass

Angelo, T.A. & Cross, K.P. (1993) Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers, 2nd Ed. Wiley Indiana University. (n.d.). Authentic assessment. Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://citl.indiana.edu/teaching-resources/assessing-student-learning/authentic-assessment/index.html

Davidson, C. N., & Katopodis, C. (2022). Estimating student workload. In The new college classroom. Harvard University Press.

Kluger, A. & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 119, No 2: 254-284.

Mueller, J. (n.d.). Authentic Assessment Toolbox. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from http://jfmueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/toolbox/index.htm

Wiggins, Grant. (1998). Ensuring authentic performance. Chapter 2 in Educative Assessment: Designing Assessments to Inform and Improve Student Performance. Jossey-Bass, pp. 21 – 42 Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Winkelmes, M. (Spring 2013). Transparency in teaching: Faculty Share data and improve student learning. Liberal Education, AAC&U, 99 (2).

- Video from researcher Dr. MaryAnn Winkelmas on the TILT framework and how it works in assignment design (Youtube).

- Transparent Assignment Template (PDF)

- Effective Assignments Worksheet Using the TILT Model (PDF)

- Checklist for Designing a Transparent Assignment copy (PDF).

Examples of Transparent Assignments

Scaffolding and Sequencing:

Scaffolding and Sequencing Writing Assignments. The Writing Center, University of Colorado, Denver. https://clas.ucdenver.edu/writing-center/sites/default/files/attached-files/scaffolding_assignments.pdf (includes a social psychology course assignment example)

Scaffolding and Sequencing Writing Assignments. University of Minnesota, Center for Writing https://wac.umn.edu/tww-program/teaching-resources/scaffolding-and-sequencing-writing-assignments (includes writing assignment examples)

Scaffolding and Assignments – How and Why. The University of Melbourne. 2021, September 15. https://le.unimelb.edu.au/news/articles/scaffolding-assignments-how-and-why

Sequencing and Scaffolding Assignments. University of Michigan, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, Sweetland Center for Writing. https://lsa.umich.edu/sweetland/instructors/teaching-resources/sequencing-and-scaffolding-assignments.html

Scaffolding Writing Assignments. Miami University, How Center for Writing Excellence. https://miamioh.edu/hcwe/hwac/teaching-support/resources-for-teaching-writing/assignment-design/scaffolding-assignments/index.html (includes practical examples of activities and assignments)

Last Modified: Monday, June 3, 2024 5:11 pm

For more information or help, please email the Office for Faculty Excellence or make an appointment with a consultant.

![]()

Teaching Resources by Montclair State University Office for Faculty Excellence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license and may be subject to additional intellectual property notices, information, or restrictions. You are solely responsible for obtaining permission to use third party content or determining whether your use is fair use and for responding to any claims that may arise.