What is the flipped classroom or flipped learning approach?

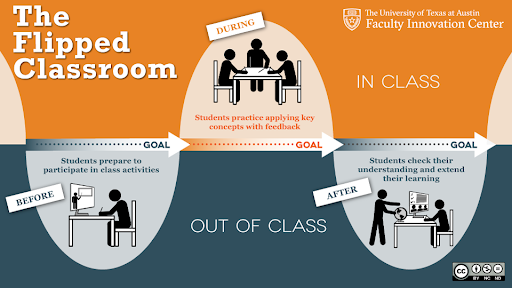

The flipped learning approach “flips” or inverts the traditional class structure. Rather than doing reading homework, listening to lectures in class, and then doing more homework, students learn course materials and concepts before class, practice applying those during class, and then have a follow-up exercise to reinforce learning. See the University of Texas at Austin’s comparison table. Flipped learning uses the unique tools of class-time, social interaction, and professor presence to clarify, extend, solidify, and complicate knowledge gained alone at home.

Three-Step Process

A. Provide engaging content to teach the lesson

- Recorded video lecture: Powerpoint with a professor on the side, providing lecture

- Professional video content from a publisher, other faculty, professional societies, public sources

- Written content — reading still counts!

- Textbook materials

- Podcasts

B. Engage the content to engage students’ minds and ensure completion

- Discussion boards

- Tip: group students to reduce reading/responding

- Blog/journal: text entries to standard or varied prompt

- Wiki/collaborative text

- Textbook questions

- Collaborative assignments

TIP: Quick grade — just complete/incomplete

Have students apply what has been learned, individually or in groups:

- Develop examples of a concept discussed in reading or homework: call on some students to report, offering corrections to teach all how the examples are and are not successful.

- Create in class: give a problem and have students solve it in class, on paper. or in another form.

- Think/pair/share on a controversial or challenging question.

- Debate prep: prepare 5-6 points for one side of a debatable question, with different students assigned different sides.

- Present new problems/case studies for students to analyze or problem-solve.

- Do further research on a topic from reading/lecture.

- Use thinking routines, a set of questions or a brief sequence of steps, to scaffold thinking (Project Zero).

- Use a jigsaw exercise: student groups become experts on subtopics and teach each other.

- Problem sets

- 1-page case study analysis

- Projects

- Create a 5-minute video lecture

- Identify and define 5 key terms

- Reflection post: explain how what you learned applies to real-life

- Another reading with questions

- Interview / find and report on an interview/article

- Complicate the perspective

- Give another view

- Deepen the investigation

MSU instructors’ examples of successful flipped learning activities:

Health assessment: each group is given a different body system to learn and present to the rest of the class; also, students had to develop a system to evaluate presentations. Complete/incomplete evaluation and peer critique. Highly engaged, worked hard, clever presentations, enjoyed by students.

Math: weekly classes, pre-quiz and post-quiz. Pre-quizzes are on the week’s topic and assess knowledge & prime the pump. Post-quizzes are based on chapter and then the quiz was often a simple MC or short answer, or questions within video. Quizzes were part of the final grade. Quiz questions were answerable if students did the homework. While the instructor worried that students would not like it, they did! Reading and reading comprehension increased.

Eric Mazur & University of Groningen, Flipped Classroom (2016)

Biology professor at Emory (2015)

Math professor at Radford (2013)

- Don’t make your own videos! Use pre-existing content when possible.

- Don’t mark and grade writing generated from engagement: assigning writing ≠ assigned grading.

- For evaluated writing, utilize light evaluation:

- Explain light evaluation–improves learning.

- Give credit for the number of words, frequency of writing.

- Grade simply: complete/incomplete.

- Assign peer feedback: students write, students read, students comment.

- Be directive in peer feedback. For example, “Read peers’ feedback and 1) Summarize in two sentences; 2) Offer a countering perspective, and 3) Offer a suggestion.

- Vary the writing to learn activities, modalities, formats, etc.

- e.g., On index cards by hand vs on a live google doc.

- e.g., Instruct to write freely or write to a specific question, etc.

Flipped Learning Network: strategies to create a “group space is transformed into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter.” (Kari Afrstrom)

Origins of Flipped Learning: Bergmann and Arfstrom, high school teachers, focused on providing content through video lecture prior to class to enable active, applied activities to enact that learning in class. Their book is Flipped Learning, and The Journal published an interview with them.

Thinking routines: Helenrose Fives’s Visible Thinking Routines and Harvard’s Project Zero.

Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

WAC, Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse: strategies to use writing to promote learning in any subject.

Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center.

Sources

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. International society for technology in education.

Graham, Steve; Michael Hebert; Writing to Read: A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Writing and Writing Instruction on Reading. Harvard Educational Review 1 December 2011; 81 (4): 710–744.

Lage, M, Platt, Gl, & Treglia, M. Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education 31 (1): 30-43.

McCrindle, A. R., & Christensen, C. A. (1995). The impact of learning journals on metacognitive and cognitive processes and learning performance. Learning and Instruction, 5(2), 167–185.

Quitadamo, I. J. and M. J. Kurtz (2007). “Learning to Improve: Using Writing to Increase Critical Thinking Performance in General Education Biology.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 6(2): 140-154.