“[C]ritically reflective teaching happens when we build into our practice the habit of constantly trying to identify, and check, the assumptions that inform our actions as teachers. The chief reason for doing this is to help us take more informed actions so that when we do something that’s intended to help students learn it actually has that effect.” (Stephen D. Brookfield, 2017, pp. 4-5)

Instructors, students, disciplinary norms, and pedagogy are all in continual flux, so even the best-prepared and skillful instructor is only such at a moment in time. Exemplary instructors model life-long learning for their students through their own engagement with their discipline, their teaching, and the ever-evolving students in their courses.

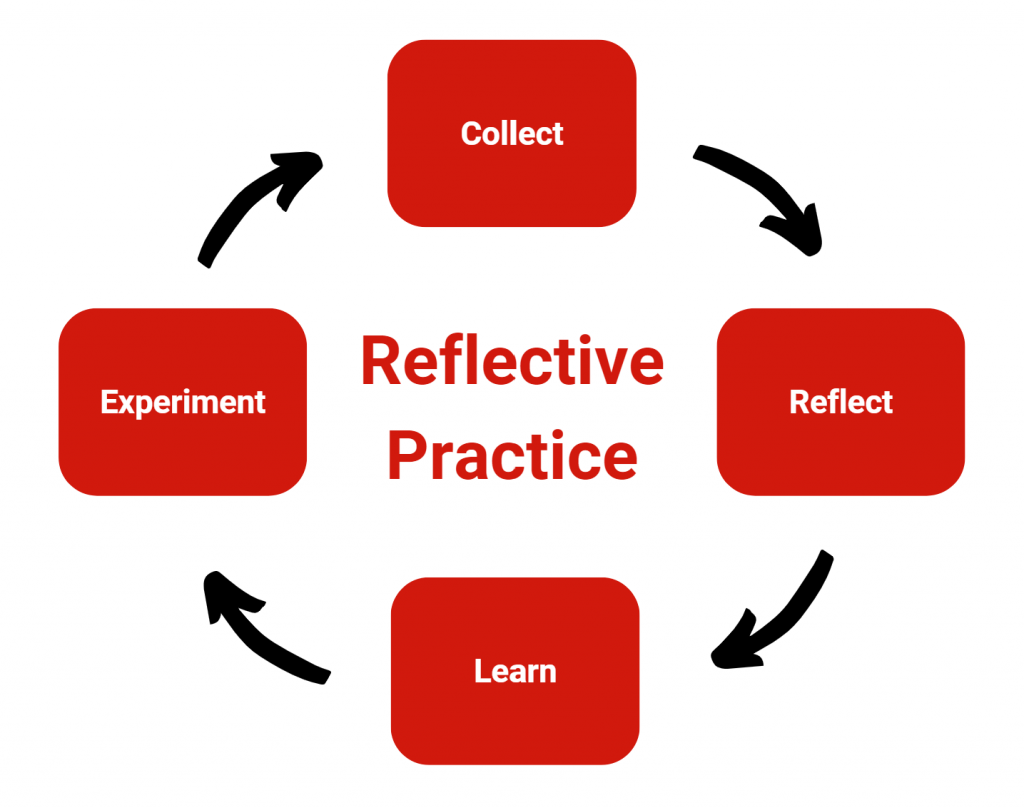

Being an effective and inclusive instructor involves regular data gathering and self-reflection, critique, ongoing learning, and experimentation. Self-reflection includes identifying personal areas of bias or weakness in teaching. Our beliefs about students, teaching, and learning feed directly into how we practice teaching. Engaging in a reflective practice ensures that our beliefs, values, and practices align through continual growth and adjustment.

Reflective practice is a Montclair teaching principle that supports all the others: reflecting as and after you design your course, as you implement supportive pedagogy, inclusivity, and universal design for learning, and as you incorporate disciplinary excellence will allow you to observe and adapt your teaching practices.

Strong instructors regularly:

- Examine their current portfolio of pedagogical strategies, even ones that have worked successfully on multiple occasions.

- Incorporate regular informal feedback from students and adapt pedagogical approaches to best support student success.

- Discover new ways to support student success:

- Explore ways to foster inclusive engagement with students.

- Experiment with teaching, proactively seeking out novel approaches, activities, and resources.

- Create and participate in communities of fellow instructors that allow for support, peer review, pedagogical strategizing, and critical engagement with teaching practices; these communities can be both informal and formal, organized by leaders who recognize the central role that reflection plays in maintaining excellent teaching.

- Repeat the cycle, beginning with further reflection.

American educational reformer John Dewey advocated reflective practice, “recogniz[ing] that the ‘thinking teacher’ requires three important attributes to be reflective; ‘open-mindedness’ to new ideas and thoughts; ‘wholeheartedness’ to seek out fresh approaches and fully engage with them; and ‘responsibility’ to be aware of the consequences of one’s own actions. So, in his view, reflections to help develop these characteristics are essential to becoming a successful teacher” (McGregor, 2011). Donald Schön (1983) identifies two forms of reflection: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-in-action occurs as you teach, allowing you to consider how things are going during the class session, and to respond and adjust as needed. It enables you to teach the “students in the room” rather than the ones you imagined as you planned. Reflection-on-action occurs after the session, as you assess how things went. Farrell (2019) proposes a third form of reflection, reflection-for-action, which involves reflection based on experience that allows instructors to anticipate what might occur. We can also consider a form of reflection-for-action that involves reflexivity, or “acting on reflections, rather than just proposing what you could have done or might do next” (McGregor & Cartwright, 2011, p. 237). Day (1999) cautions that reflection should also involve “reflection on self–one’s motivations, values, and inner life–” because teaching requires both intellectual and emotional investment and each needs to be considered.

McGregor (2011) summarizes some essential components of reflective practice:

- Actively focusing on the goals and results of your teaching;

- Establishing a pattern of reflection: collecting, assessing, and revising your teaching;

- Assessing your teaching using evidence;

- Being open-minded and committed to improving your teaching;

- Revising your pedagogy based on personal assessment and pedagogical research;

- Collaborating and consulting with peers.

Essentially, reflective teaching has two components: collecting information about your teaching, and planning your teaching development.

Collect Information about Your Teaching

Useful information for reflection can come from many sources: students, observations, and guided self-observation and reflection.

Plan Your Teaching Development

Be intentional about your teaching in the time between semesters: based on the information you collect, how should you prioritize your teaching development?

Teaching Excellence Plan

Faculty new to Montclair are encouraged to participate in the Teaching Excellence Plan, a three-year plan for developing your teaching to best support student success.

Peer Observations

Guidelines, templates, and rubrics for in-person and online courses.

Augustine. (389/1968) On the teacher. Translated by Robert P. Russell. Catholic University of America Press.

Atkinson, D. J. & Bolt, S. (2010). Using teaching observations to reflect upon and improve teaching practice in higher education. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(3), 1-19.

Barbezat, D. (2013). Contemplative Practices in Higher Education: Powerful Methods to Transform Teaching and Learning. Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. John Wiley & Sons.

Canning, R. (Aug 2004). Teaching and Learning: An Augustinian Perspective. Australian ejournal of Theology. http://aejt.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/395647/AEJT_3.4_Canning.pdf

Chick, N. (2018). SoTL in Action: Illuminating Critical Moments of Practice. Stylus.

Day, C. (1999). Researching teaching through reflective practice. In John Loughran (Ed.), Researching Teaching: Methodologies and Practices for Understanding Pedagogy, pp. 215-232.

Felten, P., Bauman, H.D.L., Kheriaty, A., & Taylor E. (2013). Transformative Conversations: A Guide to Mentoring Communities Among Colleagues in Higher Education. Jossey-Bass.

McGregor, D & Cartwright, L. (2011). Developing Reflective Practice. Open University Press.

McGregor, D. (2011). What can reflective practice mean for you . . . and why should you engage in it? In D. McGregor & L. Cartwright (Eds.), Developing Reflective Practice (pp. 1-19). McGraw-Hill Education, 2011.

Palmer, P., Zajonc, A. & Scribner, M. (2010). The Heart of Higher Education: A Call to Renewal. Jossey-Bass.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Jossey-Bass.

For more information or help, please email the Office for Faculty Excellence or make an appointment with a consultant.

10.20.23 CK

![]()

Teaching Resources by Montclair State University Office for Faculty Excellence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license and may be subject to additional intellectual property notices, information, or restrictions. You are solely responsible for obtaining permission to use third party content or determining whether your use is fair use and for responding to any claims that may arise.