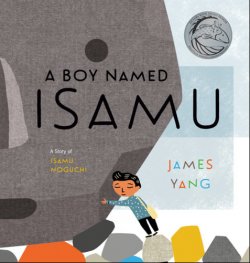

From A Boy Named Isamu by James Yang © 2021 by Penguin Random House

Reviewed By Maughn Rollins Gregory

Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) was an artist born in Los Angeles to a Japanese father and an Irish-American mother. At the age of two he moved with is mother to Tokyo, where he lived until the age of thirteen. He attended high school in Indiana and studied pre-medicine at Columbia University, until the evening classes he took at the Leonardo da Vinci School of Art convinced him to leave university to become a sculptor.

As a child, Isamu was seen as American by Japanese children, and as Japanese by American children. He learned to keep his own company and especially enjoyed exploring nature. In A Boy Named Isamu, author-illustrator James Yang imagines a day in the life of Noguchi as a young child whose curiosity and sensitivity lead him to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of his surroundings.

The story opens in a noisy, colorful market where Isamu slips away from his mother to find a quiet space. He passes children his age playing a boisterous game, and when he finally finds himself alone and in quiet, his attention is drawn to the forms, colors, and textures of objects around him. These qualities spark questions in his mind: “What kind of wood is this? How does fruit get its color? Why does cloth feel soft? Who made the path with stone? […] How can light feel so welcoming?”

From A Boy Named Isamu by James Yang © 2021 by Penguin Random House

The American philosopher John Dewey said that we should not think of art as something we only find in museums, concert halls, and the pages of great literature. He wanted us understand that the beauty and artistry we appreciate in works of fine art are not segregated from, but continuous with the qualities we enjoy in a well-made table or a loaf of good bread—and in the melody of birdsong and the patterns of a pine cone. Dewey also thought fine art should be brought out from museums into the living spaces of ordinary citizens. As a professional artist, Noguchi practiced this kind of continuity. He found ways to incorporate sculpture into people’s everyday lives, by designing playgrounds and gardens. He believed that “Art should become as one with its surroundings.”

Whether we find ourselves in a forest, a playground, a city street, or even a garbage dump, our experience is filled with varieties of color, shape, tone, texture, taste, scent, and sound. In them we can notice symmetry, harmony, intensity, pattern, and their opposites. And we naturally, even automatically, respond to these properties with strong or mild enjoyment, disgust, dis/interest, and sometimes wonder. Dewey thought that by reflecting on these experiences we can learn to be more aware of the aesthetic dimension of our experience, and to be more discerning about them: to make better judgments about the kinds of art and beauty worth enjoying and producing.

The story of Isamu reminds us that the lives of children are no less replete with aesthetic traits than are the lives of adults and that, in fact, children are often more awake to, and moved by these traits than are the adults around them. Noguchi knew this from his own experience. He once wrote that “Children […] must view the world differently from adults, their awareness of its possibilities are more primary and attuned to their capacities. When the adult would imagine like a child he must project himself into seeing the world as a totally new experience.”

How awake are we to the aesthetic features of our surroundings? Children and grownups enjoying this book might enjoy pausing to look, listen, and smell around them wherever they are to discern distinctive patterns, intense colors, strong scents, musical or dissonant sounds, and then talk about how these sensory qualities make them feel. Might any of them be translated into a drawing, poem, or song?

In this story, we see young Isamu wander into a forest and along a beach, where he stares at the color of a leaf; he tosses grass in the air and watches the blades scatter; he listens to the sound of a stick dragging through sand and to the rumble of the ocean; he makes a flute from a bamboo stalk. He feels the texture and the weight of stones and presses his ear against one to hear what it might be saying. In these scenes, Yang’s decision to narrate the entire story in the second person point of view is most effective. From the first page, Yang addresses the young reader directly: “If you were Isamu ….” In this way, youngsters reading or having this story read to them are invited to imagine themselves relating to the natural environment in the ways Isamu did.

From A Boy Named Isamu by James Yang © 2021 by Penguin Random House

Yang’s artwork here illustrates another aspect of aesthetic sensitivity: it sometimes moves us to personify members of other species, rivers, rocks, mountains, and whole landscapes. This kind of respectful, even reverential relationship to the natural world, practiced in so many indigenous cultures, is at once aesthetic and spiritual. We see ourselves in essential inter-relationship to other beings. In Noguchi’s words, we come to realize that “We are a landscape of all we have seen.”

Yang’s story emphasizes three factors that seem to enable young Isamu’s aesthetic sensitivity and artistic imagination: solitude, quietude, and being in nature. “If you are Isamu, you find a secret place so you can look at the ocean and see the shape of things.” “You feel like the only person in the world.” The short, simple sentences of Yang’s narrative and the minimalist images and subtle pallet of his artwork invite this contemplative attitude. Reading this book and pausing to pay attention to its artwork is an exercise in the very kind of discipline of attention needed to appreciate aesthetic qualities.

From A Boy Named Isamu by James Yang © 2021 by Penguin Random House

Isamu removes himself from the commotion and noise of the market and the playground to find a place he can practice careful attention. This was easier for him then than for many children now, stranded in technoscapes. Yang’s book invites readers to think about the noisy environment we take to be normal, and to consider the possibility of choosing silence sometimes. What does it feel like when outer quiet becomes inner quiet? What happens to perception when the fog of mental distraction lifts?

Young Isamu responds to his sensuous surroundings by making art. Toward the end of the book we find him back home, in his bedroom, surrounded by “sticks, pebbles, shells, and bamboo.[…] The forest and beach were like friends giving you a gift.” The adult Isamu created sculptures using a wide range of natural materials, including marble, balsa wood, basalt, granite, and water. As he once said, “For me it is the direct contact of artist to material which is original, and it is the earth and his contact to it which will free him of the artificiality of the present and his dependence on industrial products.”

Yang’s narrative ends with an image of the young artist drifting to sleep, beginning to dream of the shapes, colors, and sounds he encountered that day. “If you are Isamu, you wish every day could be this big.”

How big was my day, today?

References

Anonymous (Undated) Biography of Isama Noguchi. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden

Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2023 from https://www.noguchi.org/isamu-

noguchi/biography/biography/.

Dewey, John (1934/1987) Art as Experience. Jo Ann Boydston (Ed.) John Dewey: The Later

Works, 1925-1953, Vol. 10: 1934. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Noguchi, Isamu (1999). The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.