Maria Zbroy, Ukraine

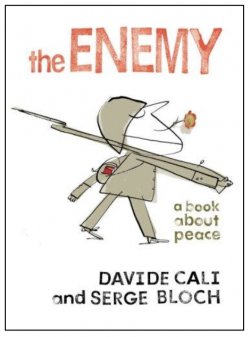

Review of The Enemy: A Book About Peace by Davide Cali, illustrated by Serge Bloch. New York: Schwartz & Wade Books, 2009. Originally published as L’Ennemi by Êditions Sarbacane, France, 2007.

It is said that the image of the enemy is the strongest motive for a soldier: it charges his weapon with bullets of hatred and fear.

Every person, society, and ethnic community builds its worldview on the basis of comparing in-group and out-group, the boundaries of which are very variable. The one who seems closest to us may be a complete stranger. And someone who comes from afar, who belongs to a completely different community or nation, can become the closest person. Only we determine who is our friend and who is our enemy. And no ideology can change this if our belief in the right is strong.

The Enemy: A Book About Peace by Davide Cali contains little text, but the book’s message and the illustrations by Serge Bloch are incredibly important. So, in front of the reader: two trenches, two holes in the ground, and inside each, a soldier. They are enemies! One tells us his story: every day he shoots at the enemy, someone he has never seen. A soldier must starve, because to start cooking is to put himself in a danger. But when the hunger becomes unbearable and the soldier lights a fire in his trench, he knows that in the next trench his enemy is lighting his own fire. Hunger is the only thing that unites them, because the enemy of the soldier is a “wild beast.” This is written in the soldier’s manual, which was given to him along with his gun. It’s also written in the manual that a soldier must kill an enemy before the enemy kills him. And if the enemy kills him, he will also kill his family and pets, burn down his forests and poison his rivers. In a word, the enemy is inhuman.

The soldier, bored with sitting in a trench, exhausted by rains, and longing for his family, thinks: maybe the war is over, we just haven’t been told about it? Maybe even the world around as we knew it no longer exists? Maybe he and his enemy are the last soldiers on earth, and the one who survives will win the war? At night, the soldier looks at the stars and thinks that maybe his enemy would like to stop the war too. He, himself, cannot be the first to stop fighting, because then the enemy will kill him. But the soldier knows that if the enemy stopped firing first, he would not kill the enemy, because, well, he himself is a man, not a monster.

Eventually, the soldier decides to break out of his trench and visit the enemy. He does not find anyone there, but sees photos of the enemy’s family, as well as a manual similar to his own. Only in it, he, our narrating soldier, is the enemy, the inhuman! But this is a lie! The soldier is indignant. “I am not the one who started this war!” He is not a monster! If only there were a way to tell that other soldier that there’s been enough fighting! And this way is found–it will be a message in a bottle, thrown by the soldier into his former trench, where he knows the enemy must be. On the second-to-last page we see two bottles, passing each other in the air, on their trajectories from each hole to the other. On the last page we see uniform rows of soldiers with two places empty. Who has won and who has lost?

I was amazed at how simple and allegorical this book is. No matter who the enemies are, each has children and families; each wants to be at home, not to dig trenches for someone else’s interests. And no one is a monster until propaganda says otherwise. What kinds of in-groups and out-groups have you and I been involved in? How did we think about people in the out-group? How did people in the out-group think about us?

But the main thing the book is about is how hard it is to dare to be the first to stop firing. This issue can be debatable, in fact, because the de-escalation of conflicts in the modern world—personal as well as international—is very complicated. Are there kinds of person-to-person or group-to-group conflict that are necessary? Davide Cali’s book shows the child that there are people on both sides of the barricades, some of whom, at least (most of whom, perhaps?) do not want a war. The soldiers in the book are simple performers who follow the manual. The decision to take up arms against someone is made by other people, far from the trenches. It is those people who create manuals, call people unlike themselves enemies, and reinforce this cult of the enemy with their propaganda. If the manual is an authority on what soldiers should think and feel and how they should act, what are the manuals in our lives?

Speaking of the modern context, in real life, we have heard reasons for war including denazification and demilitarization (the Russian war against Ukraine), the desire to change the religious beliefs of other peoples (wars in Ireland and the Middle East), even football (the 100 Hour War between El Salvador and Honduras). But if common sense is activated, can these or any others be good reasons to attack another state? Is violence ever justified? Even to defend oneself? Can we stop the war of the future? Could we have prevented it in the past?

Teachers who will read this book with children may ask the key question, What do these two enemies have in common? The answers may seem very simple: both have families, they love life, they value what they have. Probably, also, they love their homeland, if they left home to fight for it. And so, it is possible to arrive at what will stop conflicts of the future. If human life and dignity were truly the highest values, most wars, terrorist attacks, and massacres in schools would not exist. Because if you value human life–or, even, any life–above all else, how can you easily end it by pulling the trigger or pressing the button to launch a rocket? But then, if the seeds of violence are in the minds and hearts of people, how can we recognize when they begin to sprout? Is anger, resentment, even animosity sometimes justified? If so, how can we prevent it from growing into violence?

The Enemy, A Book About Peace, raises these important questions but does not answer them for us. There is not even a clear articulation in the book that it is up to each soldier to decide whether a war will take place at all—that if, at the beginning, each soldier put aside the manual and turned on his or her mind, there would be no trenches, no shelling, no separation from home. This would be a completely different book.