Artwork by Theodore Taylor III from Buzzing with Questions © 2019 by Calkins Creek

Review of Buzzing with Questions: The Inquisitive Mind of Charles Henry Turner by Janice N. Harrington, artwork by Theodore Taylor III.

New York: Calkins Creek, 2019

Reviewed By Maughn Rollins Gregory

- “Questions that itched like mosquito bites, questions that tickled like spider webs, questions you just couldn’t shoo away! Questions hopped through Charles Henry Turner’s mind like grasshoppers. His brain buzzed with questions about plants and animals and bugs.”

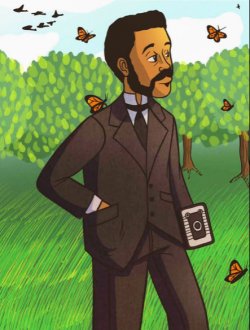

Born in Cincinnati in 1867, Charles Henry Turner’s curiosity-fueled intellect led him to the University of Cincinnati in 1886, “even though he was a janitor’s son, even though most colleges didn’t accept African American students.” In 1892 he was the first African American to earn a graduate degree from the University. He earned a PhD in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1907 and in 1910 was the first African American admitted to the St. Louis Academy of Science. As this delightful, insightful picture-book biography recounts, young Turner grew up to be a world-famous entomologist and behavioral scientist, and one of the first to study insect behavior.

As a college student, Turner found the opportunity, encouragement, and know-how to keep asking questions about the natural world. Many of his questions were about what thinking is like in non-human animals, especially insects. How much are we like ants or spiders or bees? Are they conscious in the ways we are? Philosophers following Descartes have tried to answer that question on principle, once and for all; but Turner dividied the question into several smaller questions: Are they creative? Do they have an inner clock? Do they distinguish colors? And Turner’s questions were a special kind: they could only be answered by inventing experiments. So:

To find out “if spiders could learn or if they were only weaving machines that made the same web over and over,” Turner made an arachnarium (spider jar) with sand at the bottom and an object the spider would have to incorporate into its web. Each time he replaced the object with a different one, the spider would weave a different web, leading him to conclude that spiders were using “intelligent action.”

To find out how ants find their way home, he built an ant obstacle course with cardboard platforms, rooms, and ramps. As the ants moved around the course, searching for their nest, Turner moved its pieces around, adjusted the light, painted the ramps different colors, and smeared some with stinky oil. He discovered that ants use all their senses – sight, touch, sound, and smell – to find their way home.

- To find out if bees sense time, Turner set out dishes of jam to attract local bees at breakfast, lunch, and dinner time for a while, and after he stopped the lunch and dinner feeding, the bees showed up promptly at those times anyway, expecting more jam.

- To find out if bees can see color, Turner smeared red cardboard circles with honey and set them in a patch of clover. When the bees learned that the red circles contained honey, Turner replaced the red with blue honey-smeared circles – which the bees ignored. By changing the cardboard shapes and colors in a series of 32 experiments – in which the bees consistently flew to the color red, Turner proved that bees can, indeed, see color.

What does it mean to have a mind? Do the kinds of behaviors Turner discovered in insects count? What about plants? What about rocks? These are questions most of us have wondered about since childhood. Adults sharing this book with young people might invite them to tell about a time when they wondered about the inner life of a family member, a friend, a pet, a bird or insect – and to share their own stories. But Turner’s talent for inventing thinking experiments for insects is uncommon – and instructive. This book nudges us to ask ourselves, “How would Turner approach our questions?” A teacher might even get a classroom game going: What would Turner do? (WWTD), that turns experimentation into a general mode of thinking. (It will also, inevitably make us ask, What sorts of questions can’t be answered by experiments and what other ways can we look for answers to them?)

Turner proved that cockroaches can learn to navigate a maze. He trained moths to beat their wings when he blew a whistle. Some readers will no doubt worry about the plight of the insects Turner studied – especially as they learn about the kinds of insect intelligence he discovered. (The book also describes, but does not show, “students examining the organs of small animals”). That can lead to important conversations about the ethics of using other animals for human purposes.

Artwork by Theodore Taylor III from Buzzing with Questions © 2019 by Calkins Creek

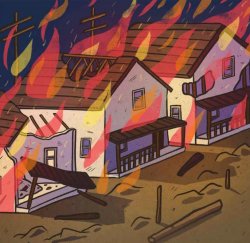

The narration of Turner’s discoveries is interrupted by a brief but arresting reference to the racism he suffered in his life, including disenfranchisement, segregation, and violence. Particular mention is made of the East St. Louis Riot of 1917, “when hateful mobs killed more than a hundred African Americans and burned their neighborhoods.” This provides historical context for Turner’s achievements and an important reminder of the origins of contemporary racial violence.

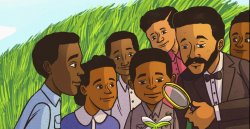

“Charles didn’t, wouldn’t, couldn’t stop asking questions.” Buzzing with Questions gives young readers a glimpse behind the textbook and the nature documentary, helping them trace knowledge backwards through a process of experimental inquiry, to its source in human questioning. Adults and children can practice together being like Turner by looking at something around them until they begin to see questions about it. This is something we can get better at. It can lead to a habit of expecting that when we pay close enough attention to something – in the natural world, in a book, or in a mind – we are sure to have questions about it. It can also lead to a conversation about different kinds of questions, the reasons for asking them, and different ways to look for answers to different kinds of questions.

Artwork by Theodore Taylor III from Buzzing with Questions © 2019 by Calkins Creek

This was, in fact, the way Turner taught his own students in schools and universities for most of his adult life. (A timeline at the end of the book mentions all his teaching appointments.) In all these schools, Turner “taught students to look closely, to find the webs that connect us all, and – just as he did – to fill the world with questions, questions, questions.”

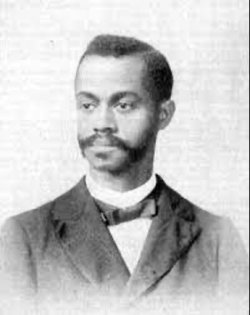

Charles Henry Turner (1867 – 1923)