Gareth B. Matthews

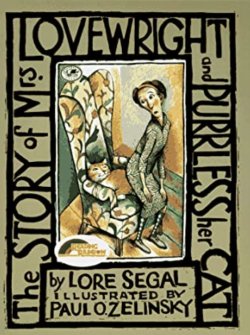

Review of The Story of Mrs. Lovewright and Purrless Her Cat by Lore Segal (Dusseldorf: Hoch-Verlag, 1974). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 6(3): 1.

Being a chilly person who lived alone, Mrs. Lovewright decided she needed a cat. She asked Dylan, who delivered her groceries, to get her one.

When Mrs. Lovewright got her cat, she named him “Purrly,” because, as she said, “he’s going to lie on my lap and purr.”

Mrs. Lovewright sat in her chair and tried to get Purrly to occupy her lap. Purrly wouldn’t. Instead, he took over Mrs. Lovewright’s footstool and refused to budge.

Mrs. Lovewright tried to get Purrly to purr. “Lie down,” she said; “I will stroke your back and you purr!” Purrly didn’t.

”Come on,” insisted Mrs. Love wright. “Don’t you know how to purr? You have to go RRRrr, RRR up, rrr down. Now you.” Purrly didn’t.

Suddenly Purrly got up and rushed down Mrs. Lovewright’s legs, giving her a scratch.

“Ouch!” Mrs. Lovewright cried.

When Dylan came another day to deliver groceries, he remarked on how much the cat had grown.

“Big enough you’d think he’d know to purr!” said Mrs. Lovewright with some exasperation. Reflecting on her exasperation Mrs. Lovewright decided to rename her cat “Purrless.” But she still kept trying to get her cat to purr. And Purrless kept responding with scratches and bites.

One evening chilly Mrs. Lovewright decided to go to bed to get warm. Purrless found the bed first and refused to make room for Mrs. Lovewright. Mrs. Lovewright tried sleeping on the edge of the bed, until Purrless stood up and, yawning, pushed Mrs. Lovewright onto the floor.

So it went. Mrs. Lovewright’s efforts to be affectionate with Purrless met with frustration, even bites. “There’s no being cozy with a cat,” she said bitterly. Mrs. Lovewright and her cat lived many years together. They learned to tolerate each other. Sometimes Mrs. Lovewright actually thought she heard Purrless purr, but she couldn’t be sure. “Don’t you want to be cozy?” she would ask him. At least he let her stroke his soft, warm, and by now enormous, back.

Cats purr. Dogs bark. Parrots mimic. Little girls play dolls. Little boys play pitch and catch. A parrot that doesn’t mimic is a failure. A little boy who doesn’t like to play ball is weird. A cat that doesn’t purr is offensive. A little girl who doesn’t like to play dolls is abnormal, unless she’s a tomboy, and then that is her nature.

Our natures determine what it is natural for us to do. And our nature fixes the kind of being we are. Cats have natures. But what can we say about a cat that doesn’t do what it is natural for cats to do?

Of course, we shouldn’t confuse natures with mere stereotypes. But how can we tell the difference? Is it by nature that a redhead has a temper? Or is that just a stereotype? Is it by nature, or only by stereotype, that dogs are obsequious to their owners, whereas cats are haughty and independent?

Having respect for a creature includes having respect for the creature’s nature. Can we have respect for the nature of a monkey, or a parrot, and yet keep the creature in a cage?

Purrless refused to conform to Mrs. Lovewright’s expectations. But what about those of us who deliberately conform to the expectations of our parents, or our friends, because we want to please them? Maybe we are cheerful, or easy-going, or clique-ish, or even bigoted, because that is what is others expect of us. They would be offended or upset if we revealed a different nature.

And do we sometimes hide behind a nature we have simply adopted? We don’t greet strangers because we are shy, shy by nature. We give up easily because we are impatient, impatient by nature. We party a great deal because we are fun-loving, just naturally fun loving.

The story of Purrless is enough to make one think again about natures, and stereotypes, about how they enter into explanations and how they make up excuses, and about whether we can always tell what is a real explanation and what is only an excuse.