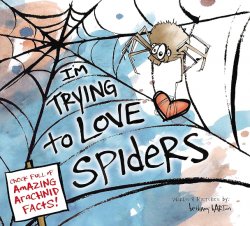

Text and artwork by Bethany Barton from I’m Trying to Love Spiders © 2019 by Puffin Books

Review of I’m Trying to Love Spiders written and illustrated by Bethany Barton

London: Puffin Books, 2019

Reviewed By Peter Shea

The narrator of I’m Trying to Love Spiders documents several forays into spider-loving, exploring spiders’ venerable history, their cleverness, their (inadvertent) service to humankind, their intricate bodies. The reader learns a lot about spiders, going along on this emotional journey. From time to time, the sheer ickiness of spiders overcomes the narrator’s noble aspirations, and the story is interrupted by “Splat.” After maybe the fourth “Splat,” emotional victory is achieved, with a last “Splat” reserved for a cockroach – the next creature on the “learning to love” list.

Barton is developing a series of “I’m Learning to Love” books; so far, she has written about garbage, rocks, math, and germs (forthcoming, 2023 – one I am eager to read, given our recent experience with COVID).

The first question I think of, reading this, is an empirical question about the project of learning to love. Don’t people just love what they love and hate what they hate? Aren’t these the basic features of their personalities? I can easily understand people disciplining their loves and hates, so that they don’t act on them. They smile at their unfavorite uncle at Thanksgiving; they swallow down the bad-tasting medicine. But can people really learn to love new things? Can they move from disgust to love by any process of reflection or inquiry or acquaintance?

In a classroom or read-aloud setting, I think that this is a question best addressed to the experience of the audience: Have you ever learned to love anything that you previously disliked or hated? What was that process like? Did information make the difference, or familiarity, or imagination? Was there one crucial experience that made the difference, or a series of small discoveries over time, or was the mere passing of time enough to make the difference?

One might also ask whether people ever moved in the opposite direction, from love to hatred or disgust, and how that happened. General Patton said, “Compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance. God help me, I do love it so.” Could one do a book like Barton’s with the title, “I’m Trying to Hate War?” (This line of inquiry, while promising, must be handled carefully, since some students may have painful memories of coming to hate that which they once loved.)

If one once establishes that there are ways of intentionally shifting loves or hates or both, it is natural to ask: When should one undertake this work? Is it worth the trouble to learn how to love spiders (as opposed to just restraining one’s impulse to kill them on sight)? Are there some things we are obliged to learn to love (our parents, our children, the natural world)?

This is philosophically rich territory: people’s ideas about their emotions, and about the ways their emotions can (and should) change are powerful, directing their growth throughout their lives. Teachers and parents can do a great service by opening a space for reflection about the power of emotion, the trustworthiness of emotion, and the ways that emotions are liable to change through reason.

It is also extremely delicate territory. The narrator in Barton’s books is not trying to override or reprogram emotion. Rather, Barton models a respectful dialogue – with oneself: “Does this change how I feel?” Splat. “Evidently not. Ok, I’ll try another approach.” This way of thinking is internal philosophical dialogue, from which one learns about love and hate, about oneself, and, along the way, about spiders. In the larger picture, this delicacy of approach is admirable, because, in many contexts, it is important to encourage children to trust their feelings. These often contain important insights (about strangers, creepy family members, dangerous situations) and they are, right or wrong, the origins of sustained action. A person who loves butterflies, or hates bullying, can build a whole life around that intuition. A book that simply debunked initial feelings (“Here’s why you should like spiders”) would be the opposite of respectful and the opposite of philosophical. Barton writes in a whimsical, exploratory way, and so models a promising way of working with negative emotions.

Barton is writing in a tradition of thoughtful, experimental treatments of emotion that includes, in philosophy, Stoic philosophers like Marcus Aurelius, as well as more recent philosophers like Martha Nussbaum, John Dewey, and Stuart Hampshire. In children’s literature, Margaret Wise Brown’s The Noisy Book introduces the reader to a dog in uncomfortable situations – unable to see, being transported in a box – who discovers that he can shift his experience by shifting his attention. Parents and teachers who wish to explore emotional choice have interesting allies.

Text and artwork by Bethany Barton from I’m Trying to Love Spiders © 2019 by Puffin Books

One other direction to take this discussion: How does it matter, and how much does it matter, for one’s education, what one loves? How are learning and love related? One can surely learn about things (spiders, math, rocks – to use Barton’s examples) without loving them, but does love make a difference to the quality or the intensity of learning? Here again, asking a group of children to tell relevant stories could start the discussion.

One thinks about a book like this initially for young children, but, with the right framing, it could be used in other contexts. In the last couple of years, semaglutide medications like Ozempic have been found to change people’s appetites in ways that are favorable to their health, giving them the ability to say, “This is what I want now, but I don’t want to want that, and taking this medication diminishes that desire.” Like Barton’s book, such medication opens up an area of choice with respect to responses that had previously been understood as immutable. People in the next decades will have to take account of these possibilities and to have discussions about what they want to love, what they want to desire, what they want to fear.