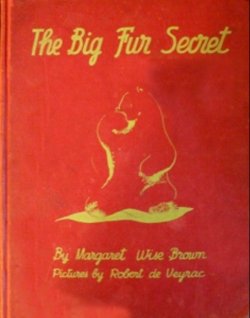

Artwork by Robert De Veyrac from The Big Fur Secret © 1944 by Harper and Brothers

Reviewed by Peter Shea

“…the eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase” – T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

Think of Margaret Wise Brown’s classic picture book, Goodnight Moon. A little rabbit (whose gender is not identified) settles down to sleep, just as a child would. Their bedroom is rich, colorful and interesting, and they say “goodnight” to each of the familiar objects – event to the mouse, who appears in a different place in each frame of the story. This story says a lot about people: we like to make ourselves at home, to get on a first-name basis with our surroundings. In the process, we sometimes make animals surrogates for ourselves – ourselves, only cuter.

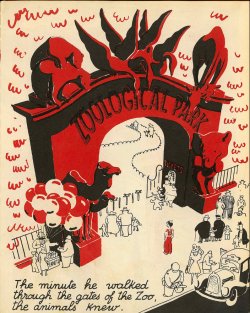

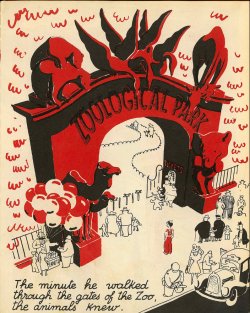

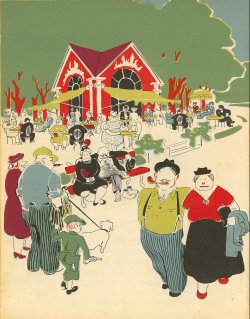

The visual world opening on page one of Brown’s The Big Fur Secret is very different. The scene is pleasant enough, when one just describes it: a boy visits the zoo. But the zoo is presented as this screaming red space, like the ominous house in a horror story, and, throughout the book, red pages alternate with milder green and blue pages. One thinks, from that first illustration, of concentration camps and refugee camps, not of a pleasant community of animals.

Artwork by Robert De Veyrac from The Big Fur Secret © 1944 by Harper and Brothers

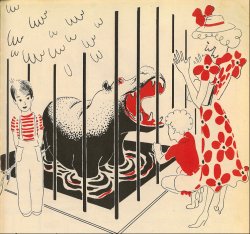

We are told that the boy and the animals share some important secret that no other human knows. The illustrations follow the boy as he watches the animals, first just observing, then having fantasies about them: of putting squirrels in his pocket, lying down beside the panda, hugging the plar bear. But he always interrupts his fantasy: the squirrel wouldn’t like to be put in a pocket; he knows better than to lie down next to a panda or to hug a polar bear.

The last part of the boy’s walk takes him past people who speak for animals: “The hippopotamus says Googly-woo.” “The gorilla wishes he had a little boy like you.” “The bear will eat you for stealing a cookie.” “The greater kadoo [kudu] is waving to you.” Though the boy doesn’t correct the adults, he knows that he knows the animals’ secret, revealed on the last page, “Animals don’t talk.”

It surely won’t escape a child at bedtime that many picture books, including some by Margaret Wise Brown, have animals talking and living in pockets and being pleasantly cuddly with humans – with the message “We are just one big, happy family – all of us animals together.” This is one way that picture books accustom children to make themselves at home in the world, to appropriate the world. It is astonishing that Brown, and Robert de Veyrac, the illustrator, have the nerve to name this appropriation and to push back against it. The zoo could mean lots of things to the animals: it is their home, perhaps their prison, perhaps their nightmare; it is not just our playground. It is a place that could have different meanings for each animals. To know that is to stop oneself from making things up, to leave room for the mystery of each animal’s consciousness.

Artwork by Robert De Veyrac from The Big Fur Secret © 1944 by Harper and Brothers

The mysterious claim of the book is that the animals know that the boy knows their secret as soon as he enters the gate. He looks at them differently. It would be fascinating to discuss whether it is possible for people and animals to recognize this difference among all the people looking at them.

The Big Fur Secret is importantly about animals, and about zoos, and about the ways people integrate defenseless beings into their projects and plots. But it is also about consciousness in a more general way: it encourages the reader (or listener) to watch watching to see seeing, and to stop short of speaking for somebody (or something) else – to hold on to the idea that how it is for us may be quite different from how it is for them. One sees this awareness in the work of the great ethologist Nikolass Tinbergen spending years trying to get closer to how a gull sees the world. But it is equally at home in everyday human relations: even beings that can talk seldom tell their whole story.

Many people have the experience of being spoken for, summarized, typecast – and it might not take much probing to elicit that kind of story, as similar to what happens routinely to animals. Some people have had their expectations overturned, their stories nullified, in interactions with pets, with family, with people they meet. Once people are conscious of how much they make up just to feel at home, in their everyday lives and interactions, they are right at the door to both science and philosophy. The Big Fur Secret helps people discover a big secret about themselves.

I think this book, now out of print and hard to find, is also a clue about the size of Margaret Wise Brown’s talent and the quality of her respect for her audience. She is not content to be just another comforting presence in children’s lives, someone to escort them toward sleep – though she does that very, very well. She wants the bedtime ritual to contain possibilities for becoming awake, for growing up, for getting beyond the clichés of the nursery. And she expects that children will value that provocation, that children are both colonizers and explorers of the world.

Artwork by Robert De Veyrac from The Big Fur Secret © 1944 by Harper and Brothers