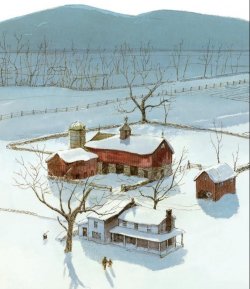

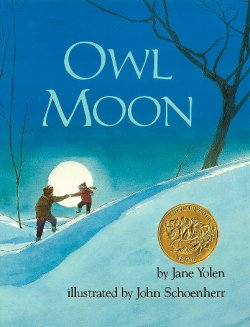

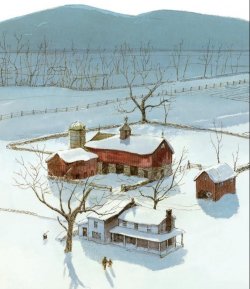

From Owl Moon, Jane Yolen (1987), illus. John Schoenherr © Philomel Books

Reviewed By Peter Shea

I started out reading thoughtfully looking over my father’s shoulder, at things he had to read for some class he was taking. Once, for a poetry class, the assignment was Robert Frost’s poem Acquainted with the Night, which contains the line, “I have outwalked the furthest city light.”

His question was, “Is that even possible, for most children, anymore?” His concern was practical: could he use this poem with sixth graders? There was also an edge of sadness in his question. He had grown up on a farm in rural North Dakota, a quarter mile from the nearest neighbor. There were no outdoor lights at night, and everyone was “acquainted with the night.” It was not something anyone bothered to mention. This difference stood in for lots of differences, including the distance separating him from his students and, to some extent, from his children. He came from a different time and a different geography. Things had different weights for him.

Owl Moon shows a father taking his daughter out into the forest, long after her bedtime, to rouse a great horned owl by hooting at it. The illustrations, for which John Schoenherr won the 1988 Caldecott Medal, make clear that the night is dark, silent, and cold – the sort of space that children are usually protected from, and kept from, by solicitous parents. The daughter has been waiting for this night a long time, and understands that they are doing something special: “going owling,” with special rules. You can’t talk. You can’t let the cold bother you. You can’t be afraid of the dark. This is a grown-up thing to do, with grown-up rules, and grown-up satisfactions: seeing something that not everybody gets to see.

And this grown-up adventure is – just a visit. There’s no use to be made of the owl. It isn’t part of a science project. That says something, also: adults visit their neighbors, including non-human neighbors.

From Owl Moon, Jane Yolen (1987), illus. John Schoenherr © Philomel Books

The counterpart to this, for some country kids, is going hunting, and reading this in rural communities will bring out those stories of this much more complex rite of passage, for older kids, and most often, for boys. If this example comes up, there’s an interesting opening to talk about different initial experiences of the non-human world, the world that, for example, comes alive at night, in the forest. In what different ways do parents introduce their children to such unfamiliar regions, and what different attitudes do the different introductions evoke?

More generally, this may well be a story that divides a class, with some children richly familiar with night adventures from wilderness camping trips and remote family cabins, and others frightened of the spaces beyond the street lights, unable to imagine feeling comfortable on a walk through the dark woods, perhaps unable to imagine that their fathers could provide enough safety and comfort for such an outing. This also can start promising conversations, as classmates come to realize the extent and variety of their differences.

It is tricky for a discussion leader to respect the beauty and integrity of Owl Moon and also to talk about it. But there is a reason to talk about it: this is too good a story to remain in the territory of fantasy, with all the elves and dragons and talking dogs. This is a real story, and the discussion leader can help make it real to children for whom such experiences are very foreign. One way to get under the skin of the story might be to ask: What is the father thinking about? and What is the daughter thinking about? Why does the father suggest – and carefully prepare – this outing, and why does the daughter look forward to it? Also, perhaps, one might ask what this kind of outing does for both of them, how they might be changed by it.

There are philosophical landscapes here to be explored. It isn’t obvious until one thinks about it a little that most people shut themselves off from some large region of their world – the dark, the night, the other side of town, the cold, the desert. We most of us live in self-gated communities, which we often take for “the world” or “reality,” and it is interesting (and, I think, important) to ask what we might be missing, as we bump up against such invisible fences. In discussion, one can ask how much limitation people take on for not enough good reason.

Another big topic: the question of what parents can give to their children, what maybe it is their job to pass on to their children, likely does not get asked enough, by either children or parents. It is natural and easy to think of parenting as constructing a safe and comfortable place for children, a fence that keeps out all the (unspecified) bad stuff. But that contract can be re-negotiated, from either side. Children can ask their parents to help them enter unfamiliar territory safely, and parents can take on the responsibility of passing on the natural experiences and realizations of their own childhoods to a new generation for whom the city lights, the new normal, put up obstacles. That kind of question, and that possibility of rethinking, is contained in any picture of an unusual parent-child interaction. A discussion might open this train of thought.

I remember being young enough to be really afraid of the dark – the monsters in the closet, the driveway out beyond the yard light. I imagine many children have such fears, and depend on their parent to help them get over them, in more or less liberating and creative ways. The father in Owl Moon invents “going owling” as a particularly brilliant way of introducing the world beyond the lights, that is, beyond what is comfortable and understood and safe. Among children young enough to remember their own fears and limits, Owl Moon might inspire helpful communication about victories and strategies – and relationships with people who help to overcome fears.

Owl Moon is suggested for children aged two through eight. I think that it might have uses with older kids also, especially those who are coming to think of themselves as taking responsibility for other people’s introduction to new territory: big brothers, swimming teachers, camp counselors, experienced athletes, beneficiaries of all kinds of experiential privilege. And, obviously, it is a powerful, provocative book for any adult teacher.

From Owl Moon, Jane Yolen (1987), illus. John Schoenherr © Philomel Books