Gareth B. Matthews

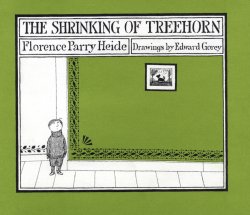

Review of The Shrinking of Treehorn by Florence Parry Heide (New York: Dell, 1971; reprinted in Treehorn Times Three, Dell, 1992). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 11(1): 1.

Treehorn noticed that he couldn’t reach the shelf in the closet where he usually hid his candy bars and bubble gum. His clothes were too big for him. He was shrinking!

Neither Treehorn’s mother nor his father took any notice of the situation. “Do sit up, Treehorn;” they told him at the dinner table. “I am sitting up;” said Treehorn; “this is as far up as I come.”

Treehorn’s mother said it was all right to pretend to be shrinking, as long as Treehorn didn’t do it at the table.

“But I am shrinking;” protested Treehorn.

“Nobody shrinks:” said Treehorn’s father, authoritatively.

When Treehorn’s parents finally did take in the fact that Treehorn was really shrinking, they didn’t know what to do. Neither did the school bus driver, or Tree horn’s teacher. When Treehorn told the school principal that he was shrinking, the principal said he was sorry. “You were right to come in;” he added; “that’s what I’m here for, to guide, not to punish, but to guide.” But he had no guidance for Treehorn.

Home again, Treehorn retreated to his room, where he found a game to play. It was called “The Big Game for Kids to Grow On.” Treehorn played, and as he played, he grew-except that when he reached the size he used to be, he stopped playing the game.

The most obvious fact that children is that they are small. A child may be too short to reach the door knocker, or to drink from the drinking fountain. Children are called, often with a condescending smile, “little people.”

Although tables and chairs at school may be the right size for children, in most of the world they are misfits. They are the naturally handicapped.

A second fact about children not quite as obvious as the first, but equally important is that they are in transition. They are growing. True, they grow at different rates. One seventh-grader may be as tall as the teacher, whereas the next one could pass for a fifth-grader. But all of them, even the tall ones, are in transition.

Of course all of us are really in transition. We’re in high school preparing for college, or in college preparing for the “real world;” or we’re single and preparing for marriage, or married and preparing for children, or in a starting position preparing to take on a management job. And all along there is the transition to death, usually associated with the “golden years:” but now with the violence in our cities and the epidemic of AIDS, increasingly associated with young people, even children.

Still, the idea of a normal progression toward becoming a standard, fully real, adult person, remains very important to us. When Treehorn deviates from this normal progression and actually shrinks (!), we sense immediately that this is either comedy or tragedy. Florence Heide’s whimsical writing style, plus Edward Gorey’s mock formal drawings, tip us off that it is, in fact, comedy.

Yet the joke is on us, especially on those of us adults who have such clear preconceptions as to how children should be developing that we fail to understand what is happening in and to a real child before us.

One thing that has made this story a favorite among children, I suspect, is the way it makes fun of adult pretense. When Treehorn’s mother finally sees that her son is shrinking, she asks her husband, “What will we do? What will people say?” “Why, they’ll say he’s getting smaller,” replies the father. But just when the father has won a few points with readers, he blows it all by adding, “I wonder if he’s doing it on purpose, just to be different” How we adults need to be in control!

The shrinking of Treehorn is a metaphor for deviance in child development. It is hard to be clear about why, and in what ways, development is really important. Most of us adults assume that our children should develop in roughly the ways we did. But that may not happen, either because they, as individuals are too different from us, or because the society in which they are growing up is too different from the one we grew up in.

One of the benefits of doing philosophy with children is that children get a chance that way to break free of adult expectations and be heard for what they themselves have to say. As one fourth grader in a school I once visited put it, “When we do philosophy, the teacher has to listen to us, too!”