Gareth B. Matthews

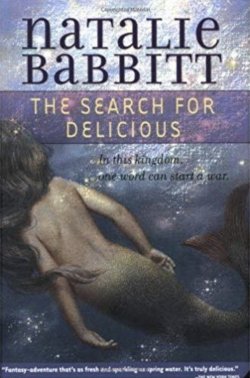

Review of The Search for Delicious by Natalie Babbitt (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1985). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 10(4): 1.

The Prime Minister was making a dictionary. He began with “Affectionate is your dog,” “Bulky is a big bag of boxes;” and “Calamitous is saying no to the king:” But he got stuck on “D:” He tried, “Delicious is fried fish:” But the King rejected that and so did the Queen, as well as the other members of the royal court. It soon became clear that there was no agreement at all within the court on what is delicious.

So the Prime Minister sent his twelve year-old stepson, Gaylen, through the whole kingdom to poll the people. Gaylen had to interview everyone and to record each person’s name, age, home, and choice for what is delicious. Soon it became clear that there was no concensus at all in the kingdom on what is delicious; in fact, each person’s choice for delicious was different from everybody else’s!

In the course of carrying out his poll, Gaylen met creatures he hadn’t known existed. He met “woldwellers” in the forest, dwarfs in a mountain, and a colorful minstrel, who gave Gaylen a magic whistle.

Before Gaylen could finish his poll, civil war broke out in the kingdom. The rebels threatened the King by cutting off the kingdom’s water supply. By means of the magic whistle, Gaylen was able to enlist the help of a mermaid, who broke the dam and released water into the kingdom again. As the water flowed once more, everyone agreed, “Delicious is a drink of water when you’re very, very thirsty.” At last the Prime Minister had an acceptable ‘D’ sentence for his dictionary. These bare bones of a plot give no hint of the magical excitement Natalie Babbitt has written into this engrossing tale. This is a fairy tale with the power of classical myth. Any child who likes fairy tales can be expected to love this one. But what about children who hate to read about dwarfs and mermaids and magic whistles? One of them might try to attack the story by going after its logic. ”A dictionary is for definitions;” the child might protest; “but Gaylen isn’t asking people for real definitions of ‘delicious’-he’s asking them to vote on what things they think are delicious; their answers to that question don’t belong in a dictionary.”

The disgruntled child would, of course, be right. There can be complete agreement on what the word ‘delicious’ means, and yet rampant disagreement on what things are, in fact delicious. Indeed, if you and I don’t mean the very same thing by ‘delicious’; we aren’t really disagreeing when I say, “The turnips are delicious;” and you say, “they aren’t delicious.”

I can imagine a teacher getting very upset at a student who tried to dismiss The Search for Delicious with this objection. The teacher’s reaction would be understandable. But it would also be unfortunate. For a protest like that can serve as a very good opportunity to think about dictionaries, and meanings of words, and what is involved in finding out what meaning a word like ‘delicious’ has.

A good place to start the discussion might be with the very notion of a definition. Dictionaries list definitions of words. But what is a definition? It is, one might say, a word or phrase that gives the meaning of another word or phrase. But what is it to give the meaning of a word or phrase? It is, one might explain further, to come up with another word or phrase that can be substituted for the word or phrase being defined without changing the meaning of what is being said.

Now it is, in fact, quite true that dictionaries have in them many definitions in that sense. But sometimes the meanings of words are explained in other ways. Under ‘hurray’ in my dictionary. For example, I find ‘used’ as an exclamation of pleasure. Now think of someone who, instead of shouting “Hurray!” shouted instead: “Used as an exclamation of pleasure!” Clearly that definition is not another way to say “Hurray!”

Then there is the question of how people make up dictionaries. Do they go around, like Gaylen, asking all sorts of other people what words mean? Or do they just ask the experts? And how do the experts find out?

There is a temptation to think that no one could know that ‘delicious’ means who hadn’t tasted something delicious. (Compare: No one can know what ‘red’ means who hasn’t seen something red). That temptation is, no doubt, part of what gives Gaylen’s project the plausibility it has.

I wouldn’t want the children in my class to focus so much on fascinating puzzles about dictionaries and meanings that they ignored everything else about The Search for Delicious. But it would also be a shame to read this story and not take advantage of the opportunity it presents to think about puzzles in the philosophy of language. They, too, can be delicious!