Gareth B. Matthews

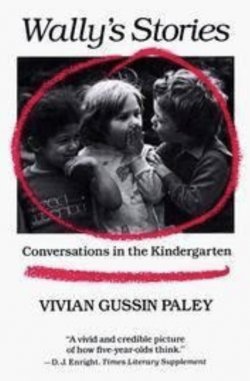

Review of Wally’s Stories by Vivian Gussin Paley (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 3(3/4): 78-79.

This is the story of a kindergarten class at the Laboratory Schools of the University of Chicago. In part it is the tale of how Wally, an impishly imaginative and highly sensitive kindergartner, began making up stories for dictation to the teacher, stories that the class then acted out. Though Wally’s natural preeminence in story-writing was never seriously threatened, eventually all the children dictated stories and all helped act out the stories they and their classmates had written.

So this is a book of kindergartners’ stories, plus commentary. But it is much more. It is also a collection of transcripts of class discussions. The teacher, Vivian Paley, follows the admirable practice of tape-recording class discussions and transcribing them daily. Good transcripts of discussions among five-year-olds are hard to find. (Piaget says there aren’t any real discussions among children of that age; but he is wrong.) This collection is the most interesting one I have seen.

Sometimes it’s a child’s story that triggers a discussion in Vivian Paley’s class; but almost anything will do. Paley herself brings all sorts of interesting issues to the class for discussion, and sometimes, decision.

“Can I be Martin Luther King, even if I’m not next on the list?” asked Wally.

“You’ll have to talk to the class,” I replied. “Tell them why you want the rule changed this time.”

Wally does.

Wally: … See, I want to be Martin Luther King. But it’s not my turn. So is it okay?

Eddie: Why do you want that, Wally?

Wally: Because my mother saw him once. And my grandmother too.

Eddie: That’s a good reason. Okay, I agree.

Everyone: Me too. (108)

Vivian Paley seems to have little interest in philosophy; yet interesting philosophical topics arise, spontaneously, in her class discussions. Consider this exchange on thinking:

Wally: … grown-ups don’t remember when they were little. They’re already an old person. Only if you have a picture of doing that. Then you could remember.

Eddie: But not thinking.

Wally: You never can take a picture of thinking. Of course not. (4)

(How one would like to continue that conversation with Wally!)

Or consider this exchange:

Eddie: But some ideas come from your mother and father.

Wally: After God puts it into their mind.

Deana: I think it just comes from your mind. Your mind tells you what to think.

Eddie: Here’ s how it happens: You remember things other people say and you see everything, and then your mind gives you spaces to keep all the rememberings and then you say it. (35)

Here’s a nice bit of conversation on wishes and ideas:

Lisa: Do plants wish for baby plants?

Deana: I think only people can make wishes. But God could put a wish inside a plant.

Teacher: What would the wish be?

Deana: What if it’s a pretty flower? Then God puts an idea inside to make this plant into a pretty red flower — if it’s supposed to be red.

Teacher: I always think of people having ideas.

Deana: It’s just the same. God puts a little idea in the plant to tell it what to be.

Sometimes a philosophical line of reflection persists in the face of a somewhat discouraging reaction from the teacher. Consider this exchange, which takes place after the class has planted lettuce seeds:

Eddie: … how do we know it’s really lettuce?

Teacher: The label says “Bibb Lettuce.”

Eddie: What if it’s really tomatoes?

Teacher: Oh. Are you wondering about the picture of tomatoes with the lettuce on the packet? It’s just an idea for a salad, after the lettuce comes up.

Warren: They might think they’re lettuce seeds and they might not grow.

Earl: Maybe the seeds look the same as something else.

Teacher: Do you think they could make such a mistake?

Lisa: Just bring it back to the store if it’s wrong.

Deana: The store people didn’t even make it.

Eddie: You have to take it back to the gardener.

Deana: Maybe they printed a word they wanted to spell the wrong way. Maybe they mixed it up.

Eddie: They could have meant to put different seeds in there and then they turned around and went to the wrong table.

Wally: The wrong part of the garden. The tomato part.

Warren: So in case it’s not lettuce it could be tomatoes. (183-4)

My family and I recently had a visitor who had grown up and lived most of her life in metropolitan areas. When we suggested taking pint boxes along on a picnic so that we could pick wild blueberries, our visitor was upset. “How will I know they are edible?” she asked. “We’ll tell you,” we said. “But then,” she replied, “you’ll put me in the awkward position of having to choose between offending you (by refusing to eat what you tell me is edible) and accepting something I have insufficient evidence for.” But how do you know to believe the labels on the berries you buy in the store?” we asked. “I’ve had lots of experience eating those,” she replied, smiling at herself.

Eddie’s question seems to be about evidence and the warrant required for real knowledge. The other children join in immediately; they happily think of various possibilities that tend to undermine the justification we might have thought we had for believing that those seeds were indeed lettuce seeds. The teacher’s summary comment is this:

There was no suggestion of robbers or magicians; human error was the only factor considered. The ideas for distributing the lettuce crop were equally practical. (184)

Clearly it was the teacher’s ideas in the dialogue that were “practical.” The children’s were more interestingly theoretical. They were trying out possibilities that might undermine a claim to know something. They were doing epistemology.

Vivian Paley obviously cares about children. She also cares about clear thinking. “Each year,” she says, “I come closer to understanding how logical thinking and precise speech can be taught in the classroom.” (213) Yet she, like almost all adults in our society, is quick to distance herself from children by a dismissive comment on their alleged irrationality. (“The endless contradictions did not offend them,” she writes on page 18; “the children did not demand consistency.” On page 137 she makes this comment: “The affirmation of an event carries its own validity — so says the child, but the adult does not agree.”)

Early on in a section called “Man in the Moon” Paley remarks, scornfully, “Inconsistency is the norm, even in wishing.” (62) There then follows the transcript of a delightful and highly ingenious discussion on whether there is a man in the moon and, if there is, how he can be there. Here are parts of it:

Earl: My cousin says you can wish on the man in the moon. I told my mother and she says it’s only pretend.

Lisa: He’s not real.

Deana: But how could he get in?

Wally: With a drill.

Eddie: The moon won’t break. It’s white like a ghost. The drill would pass in but no hole will come out.

Kenny: There is a face but my daddy says when you get up there it’s just holes. Why would that be?

Deana: Somebody could be up there making a face and then when somebody goes up there he’s gone.

Fred: There can’t be a moon man. It’s too round. He’d fall off.

Wally: He can change his shape. He gets rounder.

Eddie: The astronauts didn’t change their shape …

Fred: I saw that on television. They were walking on the moon. But a real moon man would have to find a door. And if you fall in a hole you’ll never get out.

Andy: Sure you can, when the moon is a tiny piece.

Warren: There is such a thing as a half moon. But the astronauts can’t be cut in half. They can only go when it’s round. A moon man can squeeze in half.

Eddie: There’s no air there. No air! But air is invisible so how can there be no air?

Wally: Only the moon man sees it.

Tanya: Maybe there’s a moon fairy, because some fairies are white that you could see through. (63-4)

What a marvelous discussion! (Without even a word from the teacher!) What wonderfully fresh ideas!

Imagine trying to reason out, with little knowledge of physics or astronomy, whether there could be a man in the moon. Imagine trying to put together (1) TV shots of astronauts walking on the moon, (2) pictures in books or newspapers of moon craters, (3) nursery-rhyme illustrations of the man in the moon and (4) various nighttime and, especially, daytime appearances of that mysterious object in the sky. Think about what could happen to the man in the moon when there is only a half-moon. Think about a region where there is nothing of something that, even where there is some of it, is invisible. Think about what something as wraithlike as the daytime moon might be made of.

Immediately following this lovely moon passage the teacher comments, as if in summary judgment, “The credo at age five is to believe that which makes you feel good.” (64) What a letdown! How can an adult who sets the stage for such a beautiful discussion, and records it faithfully for our great delight and instruction, see so little of its virtuosic ingenuity?

We tell our children wonderful tales of myth and magic. Then we invite them to reconcile fantasy with reality. When they fail, as we know they will, we sternly call them inconsistent. Why?

Wally’s Stories is the record of a year in a wonderful kindergarten class that is presided over by an amazingly energetic and resourceful teacher. Unfortunately that resourceful teacher has little more respect for the ruminations of children than have the more ordinary and unresourceful adults in our unphilosophical society. Still, I’m sure I’d rather be in her class than in most any available alternative.