Gareth B. Matthews

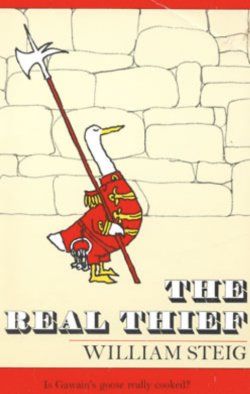

Review of The Real Thief by William Steig (New York: Farrar, Strauss &Girous, 1973). Originally published in Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 4(4-3): 1.

First it is rubies that disappear from the Royal Treasury, then gold ducats, then the famous Kalikak diamond. King Basil, the bear, is driven, quite against his inclinations, to suspect Gawain, the goose, who is the Chief Guard of the Royal Treasury and the only one, besides the King, with a key to it.

Gawain is brought to trial, found guilty, and sentenced to prison. Before he can be taken off to serve his term, though, he flies away, across Lake Superb, and hides in the forest on the other side.

The mouse, Derek, is the real thief. It had all started so innocently. He had stumbled into the Royal Treasury and had been overwhelmed by the beauty of the royal jewels. He had taken, first one, then more, and then even more, until finally he had taken the Kalikak diamond itself. He had transported all those jewels to his small, underground home among the oak roots.

Upon learning that his friend, Gawain, had been charged with the theft, Derek had resolved that, if Gawain were actually found guilty, he, Derek, would come forward and confess. But then, when Gawain had escaped, he had decided not to confess after all.

What should Derek do now? To clear Gawain’s name he steals even more jewels. Everyone soon realizes that Gawain must not have been the real thief. Then Derek returns all the jewels and goes in search of Gawain to confess and apologize.

Cleverly, Derek finds Gawain in his forest hideout, and, in a moving scene, tells him all. Gawain forgives Derek and Derek manages, with some difficulty, to get Gawain to say he will forgive the King as well. Then Gawain asks Derek, almost nonchalantly, whether he is going to confess to the others.

When I read this story aloud to others, as I often do, I stop at Gawain’s almost nonchalant question and ask my hearers what they think Derek should do and why. Should he go back and admit his misdeeds, and why, or why not? Before we finish reading the story together, we have a discussion as to how we would want it to end.

The jewels, we remind ourselves, have all been returned. The King and his subjects realize that Gawain was falsely accused and mistakenly found guilty. No doubt the King is prepared to try to make amends to Gawain. No one suspects Derek. Moreover, Derek has already suffered great remorse and taken important steps to undo his misdeeds.

Those of my hearers who suppose that the morality or immorality of an action depends essentially on the nature of that action’s consequences, are likely to conclude that Derek should not confess. Who would be made better off by such a confession? Not Derek, it seems, for he would be made to suffer even more. Not the King, it seems, for he likes Derek and would be disappointed to learn of his thievery. Not Gawain, who has already forgiven Derek and would not want him to be punished more than his remorse has already punished him.

Those of my hearers who suppose that the morality or immorality of an action is quite independent of its consequences are likely to conclude that Derek must confess. Doesn’t simply honest demand as much?

It usually happens that my hearers, whether they are adults or children, divide rather evenly into two groups those who think Derek ought not to confess and those who think he should. I give each side an opportunity to try to persuade their opponents of the correctness of their own point of view.

The point of the discussion is not to dramatize the relativity of morals. The point is rather to make clear how difficult it is to resolve serious moral dilemmas, and to show how closely intertwined questions of conscience may be with theoretical issues about what kind of consideration shows that an action is right, or wrong.

The philosophical value of Steig’s story, however, extends even beyond the fine opportunity it affords for discussing what is right, and what makes something right. Since much of the story is written, and written very sensitively, from the thief’s point of view, reading it is an exercise in the moral imagination. For Steig’s story is that rarity among children’s books an exploration of moral questions that manages to be exciting and serious, without ever being moralistic.