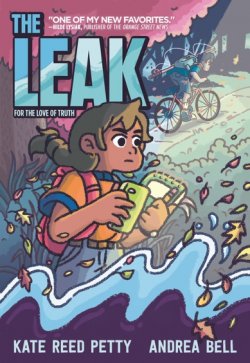

Artwork by Andrea Bell from The Leak © 2021 by First Second

Reviewed By Megan Jane Laverty and Maughn Rollins Gregory

Child activism is increasingly the subject of children’s and young adult literature. The best of these stories do more than dpict young people as insightful and heroic; they portray obstacles overcome, risks taken, and journeys through epistemological and bureaucratic mazes needed to make effective change. Such is the case for Ruth Keller, the protagonist of the middle-grade graphic novel The Leak, by Kate Reed Petty, illustrated by Andrea Bell. An aspiring 12-year-old journalist, Ruth is the founder and author of The CooOOoOOOLsLetter (newsletter) at the Twin Oaks Middle School and is looking for her next big story, when she and her friend Jonathan discover dead fish and strange black slime at the lake near their town. When Ruth decides to investigate the nature and the source of the slime, she is coached in what counts as scientific evidence by her science teacher, Ms. Freeman, who initiates a class research project on clean water and gives a history lesson on the water contamination crisis in Flint, Michigan (portrayed in a four-page interlude in the book). The novel is dedicated to the residents of Flint.

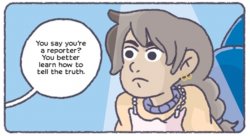

After establishing that the lake water is, in fact, contaminated and discovering that the local Twin Oaks Country Club and the Auto Spa have violated the Clean Water Act, Ruth mistakenly accuses those companies of casuing the slime – and is charged with trespassing. Eventually, she learns from her brother’s girlfriend Sarita Singh, who works for the New York Times, that a journalist needs to triangulate scientific evidence first-hand and witness observations, and other news reports, in order to find the truth. She learns, further, that when science and journalism work together, they can become powerful tools to fight injustice – but only if they maintain objectivity by not favoring pet theories or acting on suspicions.

Artwork by Andrea Bell from The Leak © 2021 by First Second

Ruth collects further samples from the lake and the groundwater that sources the town’s drinking water, and Ms. Freeman gets funding from the school principal to buy advanced kits that can detect up to 200 chemicals in the samples. The kits show that the water is polluted with chromium, lead, and barium – toxic waste that might be responsible for health problems in the community, including tooth decay and cancer. When Ruth announces in The CooOOoOOOLsLetter that she will reveal the nature and source of the contamination, the company actually responsible, Conway Power, attempts to buy her silence by offering her an education grant, funds to support her newsletter, and new equipment for the school science lab. Ruth reluctantly agrees, but at their joint press conference, she states that Conway “knows more than they’re telling us.” The novel ends with Sarita introducing Ruth to a Times reporter investigating Conway, who invites Ruth to be part of the investigation.

The power of a graphic novel depends on the synergy of text and artwork. Bell’s eye-catching artwork for The Leak propels the action of the plot, with attention to details of facial expression and body language. The colors are muted, conveying the story’s gravity. The portrayal of ethnicity in novel – mostly through the artwork – is surely intentional: Ruth is biracial, Ms. Freeman and the Times reporter are Black, Sarita is Indian American, and the school principal and company owners are White men. In this way, the book implicitly makes the point that the effects of environmental degradation are rarely suffered by those responsible for it – another point for philosophical reflection. Also significant is the fact that the protagonist and may of those who support her are female, prompting reflections on how positionality – as a child, a female, and a person of color – informs how one’s voice is heard.

An important philosophical aspect of Ruth’s story is her education in the nature of scientific and journalistic objectivity and the importance of both in environmental activism – contexts that are often left out in stories of heroes fighting the establishment. In many ways, Ruth’s story of local activism parallels that of Greta Thunberg, whose global climate activism involves utilizing media and consultation with scientists. Ruth learns that suppositions based on first-hand observations (that black slime was left by space aliens) must be tested against wider evidence (chemical analysis). She learns that jumping to conclusions (about the source of the pollutants identified in the lab) can cause harm to herself and others. Ruth also learns that those responsible for pollution may try to avoid exposure (for instance, by bribery). The Leak brings out the real complexity of social change, providing fair warning to would-be activists but also an idea of the path through difficulties.

One kind of conversation this story opens up is about how we decide what sources of information to trust, in forming our own beliefs and convictions. How can we distinguish between popular and expert opinion, fake news and responsible journalism? How can we evaluate the strength of different kinds of evidence and arguments? This conversation is vital in a day when many children and most adults carry a media production studio in their own pockets (Ruth’s smart phone is an important tool of investigation and her electronic newsletter tracks “likes” and is referenced on a famous blog).

Artwork by Andrea Bell from The Leak © 2021 by First Second

The Leak also invites conversations around personal responsibility in exposing and confronting various kinds of wrongdoing. When should I get involved in righting a wrong in my community? What kinds of problems would I need to work through, in learning and proving what is happening, and in getting people with power to pay attention? What do I need, from inside myself and from my community, to make change happen? Insights about these questions can be gained from discussing the different kinds of risks Ruth takes (alienation from friends and peers, criminal charges for trespassing, reputation as a reporter), the hardships she endured (parental disapproval, extensive time and effort, intimidation by the companies she investigated, pressure from the school principal to accept the bribe from Conway Power), the skills and virtues she exercised in doing so (indignation, critical thinking, independence, honesty, self-correction, and perseverance), and the kinds of support from others that made her successful (science tutoring from Ms. Freeman, journalistic advice from Sarita, moral support from Jonathan and her family).

As Thunberg acknowledges, even coordinated youth activism based on undisputed truth faces strident opposition from adults with vested interests – and those complicit and complacent with those interests. But the value of that activism can’t be reduced to the accomplishment of particular reforms. In the afterward, Petty advises young readers that, “You will always have a voice. It may be hard at first, but if you keep speaking up, eventually people will listen. So be sure you are speaking the truth.”